Note from the Editor:

The article below was written by @4FordFamily, a Reef2Reef staff member, however the article was also created with the help and input from @eatbreakfast @evolved @HotRocks, all prominent members of the Reef2Reef community and marine fish experts.

The wrasse photos included in this article are all healthy wrasses, not sick ones as described in the article.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

A radiant wrasse, Halichoeres iridis.

Photo is courtesy of @4FordFamily ©2019, All Rights Reserved.

What’s Wrong With My Wrasse?

Wrasse in some regards are very hardy additions to our tanks. They do, however, present a different set of challenges at the same time. Quarantining them can be difficult, for example. They don’t all handle medications as easily as their counterparts. Adding to the complication, they’re also very commonly “Typhoid Marys” for disease because of their disease resistance.

The resistance and hardiness with regard to most parasites is part of the allure for some. With thick slime coats to protect them and unique sleeping habits (mucous cocoons, sleeping under the sand, etc.) they are often difficult to target by parasites. They can even survive severe velvet infestations at times. They are obviously beautiful fish with a lot of charm. They are, however, prone to several ailments that cause them to swim “oddly” and this can be difficult for hobbyists to identify and properly treat. I will attempt to explain how to identify the ailment properly, describe the cause, and explain treatment options for these conditions.

A purple-lined wrasse, Cirrhilabrus lineatus.

Photo is courtesy of @4FordFamily ©2019, All Rights Reserved.

Spinal Injury:

A wrasse with a spinal injury will typically swim as if it has a sinker tied to its tail. The tail is generally aimed down, and the head up. The fish may spiral around the tank a bit, and barely move the back half of its body. This is often misidentified as a swim bladder infection/issue, which I will describe next. This issue has a relatively poor prognosis in many cases. The fish may seem to suddenly swim a bit off, and then over the course of a few days it will worsen. It’s not uncommon for the fish to be unable to feed, and even lay on the bottom of the tank breathing for days or even weeks as the swelling worsens. Eventually, it may succumb to the injury.

In my experience, some 25-30% of these fish seem to survive. This is only based on my own experience and observation on the forums. This seems to disproportionately impact fairy wrasses, with flasher and Halichoeres being impacted somewhat frequently as well. It can happen to any wrasse, parrotfish, or tusk, however.

Cause:

Many wrasse are particularly flighty and nervous. As a result, quick movements, lights turning on/off, aggressive tank mates, or the aggressive feeding by tank mates may startle them. These fish dart into hard lids, the side glass, or even into a rock. This is the likely cause of most of these injuries.

Recently, @Humblefish (Bobby as some of us know him) has performed autopsies of fish with presumed “spinal injuries” and has discovered uronema around the spine. This is troublesome, because what we think we know about these injuries could be completely wrong.

However, I’ve witnessed this behavior of a darting wrasse followed by this condition immediately or shortly following, so I do believe the primary cause is injury but we continue to investigate. As a precaution, feeding MetroPlex (using Seachem’s Focus to bind the medication to the food) would help treat uronema internally. However, if you do not address external uronema the chances are high that the uronema will remain. This would require treatment with MetroPlex in a quarantine tank for 14 days in conjunction with feeding the MetroPlex/Focus soaked foods. Uronema seems to be more common than it was previously.

Treatment:

There is not a lot you can do for the fish. You can try Epsom salt (pure or organic – not scented and without other additives) at a dosage of 1 tablespoon per 5 gallons, two doses 24-48 hours apart to aid the swelling. This can be administered in a quarantine tank or a display tank, as Epsom salt is essentially magnesium. Over time, the fish will still worsen but it may eventually start to slowly improve. It can take months for a fish to swim normally again, and some swim “oddly” in perpetuity but learn to adapt. And it becomes less noticeable over time.

A well-ventilated acclimation box is not a bad idea for an injured wrasse, as it keeps them from darting around and harming themselves further. This also makes it easier to “spot feed” them. Once they stop eating, it can mark the end for the fish. However, I have had some recover after a week or more without eating or moving. Euthanasia may be the best choice in some cases, but I personally wait it out as I’ve seen a couple remarkable turnarounds.

Prevention:

From a preventative point of view, a softer/gentler lid may be a better choice. Mesh lids or even egg crate can be good alternatives to harder lids. Also, avoiding quick movements near the tank, keeping children away from the glass (especially initially), and keeping wrasse with less-aggressive tank mates would be advisable.

Naoko's fairy wrasse, Cirrhilabrus naokoae.

This photo is from the Reef2Reef archives, courtesy of @Breakin Newz ©2019, All Rights Reserved.

Swim Bladder Infection/injury:

This is also somewhat common in wrasse (and other fish) but often misidentified. A couple of easy ways to tell the difference is to observe whether the fish is seemingly “overly buoyant” or if it sinks to the ground with the tail down when it does swim. A fish with a swim bladder issue generally struggles to swim downward, so it floats at the top when it stops moving.

A spinal injury will typically leave a fish less active and at the bottom of the tank. As the swim bladder issue progresses, the swim bladder of the fish will appear “swollen”. It fills up with gas, which is part of what causes the extra buoyancy.

These issues can suddenly appear about two weeks after collection of the fish from the wild. The swim bladder is an organ that aids the fish in swimming and keep it from sinking or being overly buoyant. It uses gas to achieve this result in most fish.

Causes:

This seems to be poor collection techniques, generally associated with improperly decompressing fish that were caught in deeper waters. As a result, fish caught in deeper waters are disproportionately impacted, the lineatus fairy wrasse, for example. There may be other contributing factors such as blockages in the digestive tract of the fish as well that lead to similar symptoms.

Treatment:

Antibiotics can help treat swim bladder infections. KanaPlex, MetroPlex, and Furan-2 in a quarantine for 10-14 days may help. Feeding the antibiotics may be a good move as well, adding KanaPlex would be the best bet mixed with Seachem Focus.

KanaPlex can cause “digestive movement” in fish as a side-effect, so if the issue is digestive in nature this may help on this front as well. This is also commonly considered the most effective antibiotic for swim bladder issues; the other two just cover a wider-range of infections when used together. If a digestive blockage is to blame, feeding a split green pea may help keep things moving through the fish, digestively.

Perhaps the most effective way to handle severe swim bladder infections is to actually “lance” the swim bladder. There are videos on YouTube for how to do this, but it’s not for the meek! It requires a small needle and extra points if you can gently suck air out of it with your needle (syringe). Bright light from below, a small Tupperware container, and some aluminum foil can make this a bit easier. It’s easiest to identify where the swim bladder is located when it’s swollen and full of air, but it can be tricky to locate otherwise!

Weakness/Death’s Door:

Unfortunately, a wrasse that is weak and likely near death will swim erratically. They may barrel-roll like a spinal injury might present, run in to things, sit upside down at the bottom of the tank, or even swim aggressively erratically for a few moments and suddenly drop to the bottom of the tank for a few moments.

Causes:

This can be any number of things, so it’s difficult to identify. Internal parasites are a common killer of wrasse, due to their diet in the wild they often have a disproportionate amount of internal parasites. In my opinion, it is a good idea to feed MetroPlex or General Cure (mixed with Seachem Focus to bind it to the food so it is consumed) to all new additions, but particularly wrasse. Some vehemently disagree with using antibiotics prophylactically, which is an understandable position. I am of the opinion that with wrasse it is a necessary evil.

Other causes for the decline of the fish could be poor water conditions (ammonia in particular), poor collection techniques, and any parasite. It can even be old age!

Treatment:

This depends on the cause, however, often by this stage, it is too late. Without properly identifying the ailment leading to the fish’s decline, I wouldn’t do a lot in the line of treatment at this stage (for this fish, at least). If it has velvet, ich, brook, or uronema, obviously treating for those ailments would be a good move.

Poison/Bad Reaction to Meds:

When wrasse aren’t tolerating a medication, it can cause them to swim much like they would in “Weakness/Death’s Door” outlined above. It generally starts off less severe, and progresses until the point that the fish is quite literally at death’s door. Copper is a necessary evil in many cases, but it’s also the most common medication to cause such a reaction from the wrasse. I’ve also seen them react this way to ammonia in the tank, and a mix of medications. If you mixed Prime/Amquel or any ammonia-detoxifying products with copper, this can be fatal and will likely poison your fish.

It generally presents over the course of a few days with the fish suddenly swimming “oddly”. Maneuvering less gracefully, “missing” attempts to grab food, and as it worsens possible spiraling/running in to things are commonly noted.

Treatment:

The best treatment is a water change/removal of medication. If the fish is badly afflicted with parasites or is being treated prophylactically, you may need to wait some time to try again. An established wrasse is a particularly hardy wrasse--but initially they can be quite fragile. Time has a way of making wrasse much more resilient to medications. You could try medicating the fish in a couple of weeks and increasing the level of copper (if the culprit) more slowly the second time around, or you may be better off switching treatment methods.

Chloroquine Phosphate is generally not recommended for wrasse, but little testing has been done in this regard. Early testing seemed to indicate that many wrasse cannot handle it, so it may not be advisable to use it in lieu of copper. Switching from ionic to chelated copper may be gentler, or if you started with chelated copper switching to ionic copper the second time may also yield better results. Each fish is unique, and their tolerances for certain medications will vary from other fish, even of the same species!

A yellowfin flasher wrasse, Paracheilinus flavianalis.

This photo is from the Reef2Reef archives, courtesy of @OrionN ©2019, All Rights Reserved.

Conclusion:

In short, wrasse pose a challenge for many, initially. Once established, they are fantastic additions to most tanks. Wrasse are jumpers, as mentioned, so if your tank does not have a lid you should avoid them. The unmatched beauty and grace that many wrasse bring to our slices of ocean make them quite captivating to most marine hobbyists and well worth the aggravation and research.

Also, If you choose to treat your wrasse prophylactically, some species of the Cirrhilabrus and Halichoeres genera will tolerate chloroquine phosphate. The overall consensus is that most species will not tolerate chloroquine phosphate. Therefore, copper is probably the better choice if a prophylactic treatment is preferred.

When using copper, chelated copper seems to be the least harsh of the products available. Copper should be ramped up slowly. Acclimating the fish into a QT with a chelated Cu level of +/-1.0ppm works well. Then increasing the Cu level on a daily basis of not more than .25ppm per day administered in at least two doses until you reach the desired target. (1/2 of the daily amount in the am and the other 1/2 in the pm).

~~~~~~~~~~~~

We encourage all our readers to join the Reef2Reef forum. It’s easy to register, free, and reefkeeping is much easier and more fun in a community of fellow aquarists. We pride ourselves on a warm and family-friendly forum where everyone is welcome. You will also find lots of contests and giveaways with our sponsors.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Editor Profile: @4FordFamily

@4FordFamily is a Reef2Reef staff member who is doing a lot of experiments at home, often with @HotRocks, to better understand how to both quarantine new fish and treat sick fish in order to continuously improve the standard protocols and create new ones.

He has a build thread, and we recently did a profile on him.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The article below was written by @4FordFamily, a Reef2Reef staff member, however the article was also created with the help and input from @eatbreakfast @evolved @HotRocks, all prominent members of the Reef2Reef community and marine fish experts.

The wrasse photos included in this article are all healthy wrasses, not sick ones as described in the article.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

A radiant wrasse, Halichoeres iridis.

Photo is courtesy of @4FordFamily ©2019, All Rights Reserved.

What’s Wrong With My Wrasse?

Wrasse in some regards are very hardy additions to our tanks. They do, however, present a different set of challenges at the same time. Quarantining them can be difficult, for example. They don’t all handle medications as easily as their counterparts. Adding to the complication, they’re also very commonly “Typhoid Marys” for disease because of their disease resistance.

The resistance and hardiness with regard to most parasites is part of the allure for some. With thick slime coats to protect them and unique sleeping habits (mucous cocoons, sleeping under the sand, etc.) they are often difficult to target by parasites. They can even survive severe velvet infestations at times. They are obviously beautiful fish with a lot of charm. They are, however, prone to several ailments that cause them to swim “oddly” and this can be difficult for hobbyists to identify and properly treat. I will attempt to explain how to identify the ailment properly, describe the cause, and explain treatment options for these conditions.

A purple-lined wrasse, Cirrhilabrus lineatus.

Photo is courtesy of @4FordFamily ©2019, All Rights Reserved.

Spinal Injury:

A wrasse with a spinal injury will typically swim as if it has a sinker tied to its tail. The tail is generally aimed down, and the head up. The fish may spiral around the tank a bit, and barely move the back half of its body. This is often misidentified as a swim bladder infection/issue, which I will describe next. This issue has a relatively poor prognosis in many cases. The fish may seem to suddenly swim a bit off, and then over the course of a few days it will worsen. It’s not uncommon for the fish to be unable to feed, and even lay on the bottom of the tank breathing for days or even weeks as the swelling worsens. Eventually, it may succumb to the injury.

In my experience, some 25-30% of these fish seem to survive. This is only based on my own experience and observation on the forums. This seems to disproportionately impact fairy wrasses, with flasher and Halichoeres being impacted somewhat frequently as well. It can happen to any wrasse, parrotfish, or tusk, however.

Cause:

Many wrasse are particularly flighty and nervous. As a result, quick movements, lights turning on/off, aggressive tank mates, or the aggressive feeding by tank mates may startle them. These fish dart into hard lids, the side glass, or even into a rock. This is the likely cause of most of these injuries.

Recently, @Humblefish (Bobby as some of us know him) has performed autopsies of fish with presumed “spinal injuries” and has discovered uronema around the spine. This is troublesome, because what we think we know about these injuries could be completely wrong.

However, I’ve witnessed this behavior of a darting wrasse followed by this condition immediately or shortly following, so I do believe the primary cause is injury but we continue to investigate. As a precaution, feeding MetroPlex (using Seachem’s Focus to bind the medication to the food) would help treat uronema internally. However, if you do not address external uronema the chances are high that the uronema will remain. This would require treatment with MetroPlex in a quarantine tank for 14 days in conjunction with feeding the MetroPlex/Focus soaked foods. Uronema seems to be more common than it was previously.

Treatment:

There is not a lot you can do for the fish. You can try Epsom salt (pure or organic – not scented and without other additives) at a dosage of 1 tablespoon per 5 gallons, two doses 24-48 hours apart to aid the swelling. This can be administered in a quarantine tank or a display tank, as Epsom salt is essentially magnesium. Over time, the fish will still worsen but it may eventually start to slowly improve. It can take months for a fish to swim normally again, and some swim “oddly” in perpetuity but learn to adapt. And it becomes less noticeable over time.

A well-ventilated acclimation box is not a bad idea for an injured wrasse, as it keeps them from darting around and harming themselves further. This also makes it easier to “spot feed” them. Once they stop eating, it can mark the end for the fish. However, I have had some recover after a week or more without eating or moving. Euthanasia may be the best choice in some cases, but I personally wait it out as I’ve seen a couple remarkable turnarounds.

Prevention:

From a preventative point of view, a softer/gentler lid may be a better choice. Mesh lids or even egg crate can be good alternatives to harder lids. Also, avoiding quick movements near the tank, keeping children away from the glass (especially initially), and keeping wrasse with less-aggressive tank mates would be advisable.

Naoko's fairy wrasse, Cirrhilabrus naokoae.

This photo is from the Reef2Reef archives, courtesy of @Breakin Newz ©2019, All Rights Reserved.

Swim Bladder Infection/injury:

This is also somewhat common in wrasse (and other fish) but often misidentified. A couple of easy ways to tell the difference is to observe whether the fish is seemingly “overly buoyant” or if it sinks to the ground with the tail down when it does swim. A fish with a swim bladder issue generally struggles to swim downward, so it floats at the top when it stops moving.

A spinal injury will typically leave a fish less active and at the bottom of the tank. As the swim bladder issue progresses, the swim bladder of the fish will appear “swollen”. It fills up with gas, which is part of what causes the extra buoyancy.

These issues can suddenly appear about two weeks after collection of the fish from the wild. The swim bladder is an organ that aids the fish in swimming and keep it from sinking or being overly buoyant. It uses gas to achieve this result in most fish.

Causes:

This seems to be poor collection techniques, generally associated with improperly decompressing fish that were caught in deeper waters. As a result, fish caught in deeper waters are disproportionately impacted, the lineatus fairy wrasse, for example. There may be other contributing factors such as blockages in the digestive tract of the fish as well that lead to similar symptoms.

Treatment:

Antibiotics can help treat swim bladder infections. KanaPlex, MetroPlex, and Furan-2 in a quarantine for 10-14 days may help. Feeding the antibiotics may be a good move as well, adding KanaPlex would be the best bet mixed with Seachem Focus.

KanaPlex can cause “digestive movement” in fish as a side-effect, so if the issue is digestive in nature this may help on this front as well. This is also commonly considered the most effective antibiotic for swim bladder issues; the other two just cover a wider-range of infections when used together. If a digestive blockage is to blame, feeding a split green pea may help keep things moving through the fish, digestively.

Perhaps the most effective way to handle severe swim bladder infections is to actually “lance” the swim bladder. There are videos on YouTube for how to do this, but it’s not for the meek! It requires a small needle and extra points if you can gently suck air out of it with your needle (syringe). Bright light from below, a small Tupperware container, and some aluminum foil can make this a bit easier. It’s easiest to identify where the swim bladder is located when it’s swollen and full of air, but it can be tricky to locate otherwise!

Weakness/Death’s Door:

Unfortunately, a wrasse that is weak and likely near death will swim erratically. They may barrel-roll like a spinal injury might present, run in to things, sit upside down at the bottom of the tank, or even swim aggressively erratically for a few moments and suddenly drop to the bottom of the tank for a few moments.

Causes:

This can be any number of things, so it’s difficult to identify. Internal parasites are a common killer of wrasse, due to their diet in the wild they often have a disproportionate amount of internal parasites. In my opinion, it is a good idea to feed MetroPlex or General Cure (mixed with Seachem Focus to bind it to the food so it is consumed) to all new additions, but particularly wrasse. Some vehemently disagree with using antibiotics prophylactically, which is an understandable position. I am of the opinion that with wrasse it is a necessary evil.

Other causes for the decline of the fish could be poor water conditions (ammonia in particular), poor collection techniques, and any parasite. It can even be old age!

Treatment:

This depends on the cause, however, often by this stage, it is too late. Without properly identifying the ailment leading to the fish’s decline, I wouldn’t do a lot in the line of treatment at this stage (for this fish, at least). If it has velvet, ich, brook, or uronema, obviously treating for those ailments would be a good move.

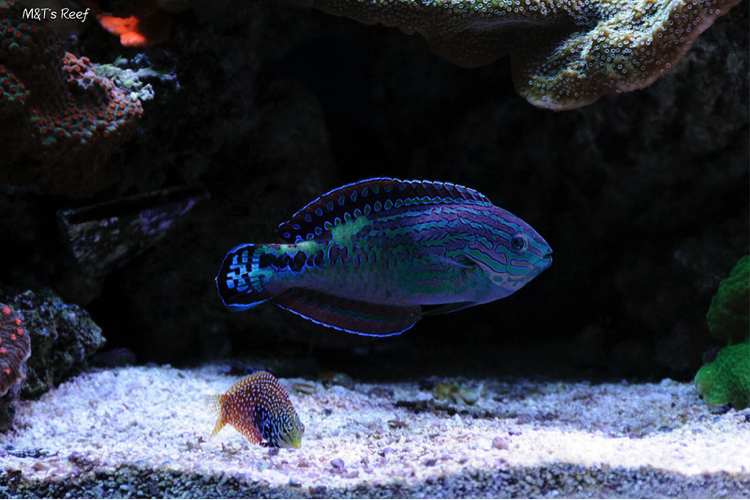

A male blue star leopard wrasse, Macropharyngodon bipartitus.

This photo is from the Reef2Reef archives, courtesy of @Mike&Terry ©2019, All Rights Reserved.

This photo is from the Reef2Reef archives, courtesy of @Mike&Terry ©2019, All Rights Reserved.

Poison/Bad Reaction to Meds:

When wrasse aren’t tolerating a medication, it can cause them to swim much like they would in “Weakness/Death’s Door” outlined above. It generally starts off less severe, and progresses until the point that the fish is quite literally at death’s door. Copper is a necessary evil in many cases, but it’s also the most common medication to cause such a reaction from the wrasse. I’ve also seen them react this way to ammonia in the tank, and a mix of medications. If you mixed Prime/Amquel or any ammonia-detoxifying products with copper, this can be fatal and will likely poison your fish.

It generally presents over the course of a few days with the fish suddenly swimming “oddly”. Maneuvering less gracefully, “missing” attempts to grab food, and as it worsens possible spiraling/running in to things are commonly noted.

Treatment:

The best treatment is a water change/removal of medication. If the fish is badly afflicted with parasites or is being treated prophylactically, you may need to wait some time to try again. An established wrasse is a particularly hardy wrasse--but initially they can be quite fragile. Time has a way of making wrasse much more resilient to medications. You could try medicating the fish in a couple of weeks and increasing the level of copper (if the culprit) more slowly the second time around, or you may be better off switching treatment methods.

Chloroquine Phosphate is generally not recommended for wrasse, but little testing has been done in this regard. Early testing seemed to indicate that many wrasse cannot handle it, so it may not be advisable to use it in lieu of copper. Switching from ionic to chelated copper may be gentler, or if you started with chelated copper switching to ionic copper the second time may also yield better results. Each fish is unique, and their tolerances for certain medications will vary from other fish, even of the same species!

A yellowfin flasher wrasse, Paracheilinus flavianalis.

This photo is from the Reef2Reef archives, courtesy of @OrionN ©2019, All Rights Reserved.

Conclusion:

In short, wrasse pose a challenge for many, initially. Once established, they are fantastic additions to most tanks. Wrasse are jumpers, as mentioned, so if your tank does not have a lid you should avoid them. The unmatched beauty and grace that many wrasse bring to our slices of ocean make them quite captivating to most marine hobbyists and well worth the aggravation and research.

Also, If you choose to treat your wrasse prophylactically, some species of the Cirrhilabrus and Halichoeres genera will tolerate chloroquine phosphate. The overall consensus is that most species will not tolerate chloroquine phosphate. Therefore, copper is probably the better choice if a prophylactic treatment is preferred.

When using copper, chelated copper seems to be the least harsh of the products available. Copper should be ramped up slowly. Acclimating the fish into a QT with a chelated Cu level of +/-1.0ppm works well. Then increasing the Cu level on a daily basis of not more than .25ppm per day administered in at least two doses until you reach the desired target. (1/2 of the daily amount in the am and the other 1/2 in the pm).

~~~~~~~~~~~~

We encourage all our readers to join the Reef2Reef forum. It’s easy to register, free, and reefkeeping is much easier and more fun in a community of fellow aquarists. We pride ourselves on a warm and family-friendly forum where everyone is welcome. You will also find lots of contests and giveaways with our sponsors.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Editor Profile: @4FordFamily

@4FordFamily is a Reef2Reef staff member who is doing a lot of experiments at home, often with @HotRocks, to better understand how to both quarantine new fish and treat sick fish in order to continuously improve the standard protocols and create new ones.

He has a build thread, and we recently did a profile on him.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~