In this aquarium I can maintain phosphates in the range 0,03-0,05 when dosing NP-bacto-balance. It always depends on the different between production and exporting/reducing (like the carbon dosing)

Navigation

Install the app

How to install the app on iOS

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature may not be available in some browsers.

More options

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Dinoflagelates. A disruptive treatment

- Thread starter Beuchat

- Start date

- Tagged users None

According to Tropic Marin usage of Elimi-NP should reduce phosphate to the bottom limit (0,03), and then you should switch to Bact-NP to keep phosphates at bay.

My experience is quite different. I have been using Elimi-NP for the last nine months and my phosphate level never dropped below 0,15. I reached that bottom limit when nitrate was 0, what means that nitrate would then be the limiting factor and it would become imposible to lower more the phosphate concentration. Afterwards, I managed to increase nitrate to 4,6 and then phosphate increased to 0,24.

I have quite a wide experience using carbon sources to reduce nutrients. I have used Nopox, vodka/vinegar and Elimi-NP, either separately or in combination of two of them. All of these carbon sources are pretty effective to reduce nitrate but not to reduce phosphate.

In my opinion the main problem here is the unknown variable in the strategy. And this variable has a microbiological nature. Carbon sources do not lower nutrients by themselves, but by promoting the growth of bacterial populations that use those nutrients. And the naked truth is that we do not know what bacterial species we have in our tanks. Actually we do not even know what bacterial species we put when we add bacterial formulations, because the companies do not say it.

In the absence of such information the strategies based on bacterial growth to promote nutrient reduction can not be universally effective. Also, the strategies designed to combat dinos based on nutrient reduction can not be universally effective. These strategies are based on ecological changes induced by competition between microorganisms, but we do not know what bacterial species are specially good at competing with dinos. Should all of them be equally good, then nutrient reduction would always work at eliminating dinos. However, the experience (my experience, too) tell us it is not that way.

Find the adequate bacterial species to compete with dinos, then feed them (and most likely any carbon source will be good enough to do it) and the problem will be solved.

My experience is quite different. I have been using Elimi-NP for the last nine months and my phosphate level never dropped below 0,15. I reached that bottom limit when nitrate was 0, what means that nitrate would then be the limiting factor and it would become imposible to lower more the phosphate concentration. Afterwards, I managed to increase nitrate to 4,6 and then phosphate increased to 0,24.

I have quite a wide experience using carbon sources to reduce nutrients. I have used Nopox, vodka/vinegar and Elimi-NP, either separately or in combination of two of them. All of these carbon sources are pretty effective to reduce nitrate but not to reduce phosphate.

In my opinion the main problem here is the unknown variable in the strategy. And this variable has a microbiological nature. Carbon sources do not lower nutrients by themselves, but by promoting the growth of bacterial populations that use those nutrients. And the naked truth is that we do not know what bacterial species we have in our tanks. Actually we do not even know what bacterial species we put when we add bacterial formulations, because the companies do not say it.

In the absence of such information the strategies based on bacterial growth to promote nutrient reduction can not be universally effective. Also, the strategies designed to combat dinos based on nutrient reduction can not be universally effective. These strategies are based on ecological changes induced by competition between microorganisms, but we do not know what bacterial species are specially good at competing with dinos. Should all of them be equally good, then nutrient reduction would always work at eliminating dinos. However, the experience (my experience, too) tell us it is not that way.

Find the adequate bacterial species to compete with dinos, then feed them (and most likely any carbon source will be good enough to do it) and the problem will be solved.

Hi Chema, I agree with you. The objetive of this strategy is to feed heterotrophic bacteria to release allelopathy compounds that provoque the dino recession. The nutrient reduction is a side effect of the treatment. IMO dinos can not be eliminated only with nutrient depletion itself.

Hi Beuchat: I prefer the term competition because it includes more ways to reduce an antagonist population than biochemical warfare or allelopathy (for example competition for space).

I'm not aware of any scientific report that demonstrate the production of toxins or other allelopathy compounds by heterotrophic bacteria natural inhabitants of reef tanks that promote reduction of dino populations. However, there are many examples of the opposite: dinoflagellate species able to produce toxic compounds against bacteria, diatoms and macroalgae (Wang et al., 2020; Fernández-Herrera et al., 2021; Wu et al., 2021). Also, there are some reports on the production of compounds by diatoms which are able to target dinoflagellates (Xu et al., 2019; Picherri et al., 2017).

In my experience, when I got maximum reduction of nutrients (0 nitrates, 0,15 phosphate) I got more cyano and less dinos. The best reduction in dinos (but no elimination ) was achieved by silica dosing and, thus, promotion of diatom growth (not only theoretical, I took sand samples and could observe it).

I'm not aware of any scientific report that demonstrate the production of toxins or other allelopathy compounds by heterotrophic bacteria natural inhabitants of reef tanks that promote reduction of dino populations. However, there are many examples of the opposite: dinoflagellate species able to produce toxic compounds against bacteria, diatoms and macroalgae (Wang et al., 2020; Fernández-Herrera et al., 2021; Wu et al., 2021). Also, there are some reports on the production of compounds by diatoms which are able to target dinoflagellates (Xu et al., 2019; Picherri et al., 2017).

In my experience, when I got maximum reduction of nutrients (0 nitrates, 0,15 phosphate) I got more cyano and less dinos. The best reduction in dinos (but no elimination ) was achieved by silica dosing and, thus, promotion of diatom growth (not only theoretical, I took sand samples and could observe it).

Hi Chema,

As we normally don't have the right resources and funds to conduct precise scientific testing in our tanks (to reach 100% reliable conclusions), we usually relay on scientific papers, as the ones you mention, to support our assumptions. For additional clarification I copy hereby an excerpt from my article about the action mechanism behind this treatment:

I have not used silica dosing to fight dinos. My assumption is that the silica dosing improve the competition from diatoms in the form of dino displacement as a consequence of stealing nutrient, space, light and the existence of allopathic interactions, like PUAS released in the water. As you highlight, there are several studies where dinoflagellates cells are inhibited by exudates filtered from diatoms cultures.

The reciprocal actions among microscopic organism in our tanks (bacteria, protists, phytoplankton and zooplankton ) is so complex (depending on autotrophy, heterotrophy, photosynthesis activity, nutrient availability, light and chemical conditions) that is virtually Imposible to establish a 100% reliable model of global interaction. I believe we can only evaluate partial interactions.

I hope is more clear now.

As we normally don't have the right resources and funds to conduct precise scientific testing in our tanks (to reach 100% reliable conclusions), we usually relay on scientific papers, as the ones you mention, to support our assumptions. For additional clarification I copy hereby an excerpt from my article about the action mechanism behind this treatment:

""The biological mechanism underlying is the combined effect of two factors that cause the dinoflagellate populations to be reduced.

1- Bacteria "steal" food from the dinoflagellates. Due to the addition of organic carbon, the heterotrophic bacteria that are housed in the sand, the rocks and other surfaces of the aquarium, start to reproduce in an extraordinary way, removing nitrate, phosphate and trace elements from the water. They form biofilms that spread on all available surfaces, displacing dinoflagellates.

2- Bacteria directly inhibit the growth of dinoflagellate cells through allelopathy (chemical warfare). The survival strategy of bacteria, protists and phytoplankton, includes a line of defense, which consists of releasing chemical compounds toxic to other species. For example, as a result of copepod predation on diatoms, the algae produce polyunsaturated aldehydes (PUAS), which are noxious to copepods and some phytoplankton species, such as urchin larvae. These PUAS are also produced by other phytoplankton species, such as cyanobacteria, cryptophytes, primnesiophytes, and synurophytes. In addition, PUAS have a potent inhibitory effect on the growth of the dinoflagellate Ostreopsis ovata, altering its DNA structure and disrupting its development.

Figures 2 to show the evolution of 2 of the of the 11 aquaria where the essay was carried out. The addition of organic carbon, allows the heterotrophic bacterial communities to reproduce and generate their allelopathy compounds, which inhibit the growth of dinoflagellates. In the following scientific study: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2015.00100/full, it is explained how the dinoflagellate Alexandrium tamarense is inhibited by allelopathy compounds generated by marine bacteria Brevibacterium, Thalassobius, Alteromonoas, Rhodobacteracea, Pseudoalteromonas, Vibrio and Halomonas. According to the article, there is a the regression of the cells of Alexandrium tamarense after 10 min, 30 min and 24 h, because of the introduction of the bacteria. The aforementioned study has been kindly shared by Postdoctoral Researcher. Mrs. Esther Garcés, who is a scientific authority in the field of dinoflagellates."""

I have not used silica dosing to fight dinos. My assumption is that the silica dosing improve the competition from diatoms in the form of dino displacement as a consequence of stealing nutrient, space, light and the existence of allopathic interactions, like PUAS released in the water. As you highlight, there are several studies where dinoflagellates cells are inhibited by exudates filtered from diatoms cultures.

The reciprocal actions among microscopic organism in our tanks (bacteria, protists, phytoplankton and zooplankton ) is so complex (depending on autotrophy, heterotrophy, photosynthesis activity, nutrient availability, light and chemical conditions) that is virtually Imposible to establish a 100% reliable model of global interaction. I believe we can only evaluate partial interactions.

I hope is more clear now.

Hi Beuchat: I prefer the term competition because it includes more ways to reduce an antagonist population than biochemical warfare or allelopathy (for example competition for space).

I'm not aware of any scientific report that demonstrate the production of toxins or other allelopathy compounds by heterotrophic bacteria natural inhabitants of reef tanks that promote reduction of dino populations. However, there are many examples of the opposite: dinoflagellate species able to produce toxic compounds against bacteria, diatoms and macroalgae (Wang et al., 2020; Fernández-Herrera et al., 2021; Wu et al., 2021). Also, there are some reports on the production of compounds by diatoms which are able to target dinoflagellates (Xu et al., 2019; Picherri et al., 2017).

In my experience, when I got maximum reduction of nutrients (0 nitrates, 0,15 phosphate) I got more cyano and less dinos. The best reduction in dinos (but no elimination ) was achieved by silica dosing and, thus, promotion of diatom growth (not only theoretical, I took sand samples and could observe it).

Hi BeuchatHi Chema,

As we normally don't have the right resources and funds to conduct precise scientific testing in our tanks (to reach 100% reliable conclusions), we usually relay on scientific papers, as the ones you mention, to support our assumptions. For additional clarification I copy hereby an excerpt from my article about the action mechanism behind this treatment:

""The biological mechanism underlying is the combined effect of two factors that cause the dinoflagellate populations to be reduced.

1- Bacteria "steal" food from the dinoflagellates. Due to the addition of organic carbon, the heterotrophic bacteria that are housed in the sand, the rocks and other surfaces of the aquarium, start to reproduce in an extraordinary way, removing nitrate, phosphate and trace elements from the water. They form biofilms that spread on all available surfaces, displacing dinoflagellates.

2- Bacteria directly inhibit the growth of dinoflagellate cells through allelopathy (chemical warfare). The survival strategy of bacteria, protists and phytoplankton, includes a line of defense, which consists of releasing chemical compounds toxic to other species. For example, as a result of copepod predation on diatoms, the algae produce polyunsaturated aldehydes (PUAS), which are noxious to copepods and some phytoplankton species, such as urchin larvae. These PUAS are also produced by other phytoplankton species, such as cyanobacteria, cryptophytes, primnesiophytes, and synurophytes. In addition, PUAS have a potent inhibitory effect on the growth of the dinoflagellate Ostreopsis ovata, altering its DNA structure and disrupting its development.

Figures 2 to show the evolution of 2 of the of the 11 aquaria where the essay was carried out. The addition of organic carbon, allows the heterotrophic bacterial communities to reproduce and generate their allelopathy compounds, which inhibit the growth of dinoflagellates. In the following scientific study: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2015.00100/full, it is explained how the dinoflagellate Alexandrium tamarense is inhibited by allelopathy compounds generated by marine bacteria Brevibacterium, Thalassobius, Alteromonoas, Rhodobacteracea, Pseudoalteromonas, Vibrio and Halomonas. According to the article, there is a the regression of the cells of Alexandrium tamarense after 10 min, 30 min and 24 h, because of the introduction of the bacteria. The aforementioned study has been kindly shared by Postdoctoral Researcher. Mrs. Esther Garcés, who is a scientific authority in the field of dinoflagellates."""

I have not used silica dosing to fight dinos. My assumption is that the silica dosing improve the competition from diatoms in the form of dino displacement as a consequence of stealing nutrient, space, light and the existence of allopathic interactions, like PUAS released in the water. As you highlight, there are several studies where dinoflagellates cells are inhibited by exudates filtered from diatoms cultures.

The reciprocal actions among microscopic organism in our tanks (bacteria, protists, phytoplankton and zooplankton ) is so complex (depending on autotrophy, heterotrophy, photosynthesis activity, nutrient availability, light and chemical conditions) that is virtually Imposible to establish a 100% reliable model of global interaction. I believe we can only evaluate partial interactions.

I hope is more clear now

What do you explain in the first paragraph is competition, as I formerly stated in my post.

In the second paragraph you try to support that heterotrophic bacteria produce compounds that inhibit the growth or directly kill dinoflagellates by citing a scientific report that supposedly confirms that point. After carefully reading the results presented in that paper (Hu et al., 2015), I found no evidence for the production of such compounds . The fourth section of Results ("Algicidal effects of bacteria on the growth of A. tamariensis") shows the results of an experiment where the incubation of a culture of the dinoflagellate Alexandrium tamarense with bacteria isolated from the phycosphere resulted in the lysis of A. tamarense cells. However, the study provides no evidence regarding the toxins or allelopathy compounds that you assume are responsible for the lysis. Furthermore, the authors do not even suggest that such compounds may be responsible for the killing of the dinoflagellate and they only confirm that "when treated by high density bacteria (10 to the ninth cells/ml), the cells of A. tamarensis were lysed and degraded into debris in 24 h." (see Discussion).

I'm not denying the possibility that certain bacteria may produce toxins that negatively affect dinoflagellates. I'm stating that I have not been able to find any scientific report confirming it and that the one you cite do not support allelopathy as the cause of dinoflagellate killing by bacteria, and much less contains "an explanation of how allelopathy compounds generated by marine bacteria inhibit A. tamarensis".

By the way, I have also published some papers in Frontiers, but in Frontiers in Microbiology and Frontiers in Plant Science.

Hi Chema, you are right. I quoted a different paper. I had two of them when we were discussing among the people in the test group. The first one was provided by Esther Garcés and this second one by one of the aquarist performing the test.

www.sciencedirect.com

www.sciencedirect.com

If you publish scientific documents you will have a better background than me to interpret this documentation. IMO the deterioration of dino cells just 10 minutes after the addition of the bacteria is a strong evidence of a chemical interaction

Investigation of the algicidal exudate produced by Shewanella sp. IRI-160 and its effect on dinoflagellates

The bacterium, Shewanella sp. IRI-160, was previously shown to have negative effects on the growth of dinoflagellates, while having no negative effect…

If you publish scientific documents you will have a better background than me to interpret this documentation. IMO the deterioration of dino cells just 10 minutes after the addition of the bacteria is a strong evidence of a chemical interaction

- Joined

- Mar 10, 2018

- Messages

- 98

- Reaction score

- 60

Very nice investigation. While using the Xepta NP, should my skimmer remain on through out the reduction process?THE PROBLEM

As is well known, dinoflagellate pests in the reef aquarium are perhaps the worst that we will face during the life of our system. These pests are quite difficult to eradicate because dinoflagellates have a great capacity for reproduction, propagation and survival. In addition, measures that are effective for one species are not equally valid for others. To complicate matters, aquarium history and environmental variables, e.g., existing nitrate and phosphate concentrations or, more specifically, the variation of these, play an extraordinarily relevant role.

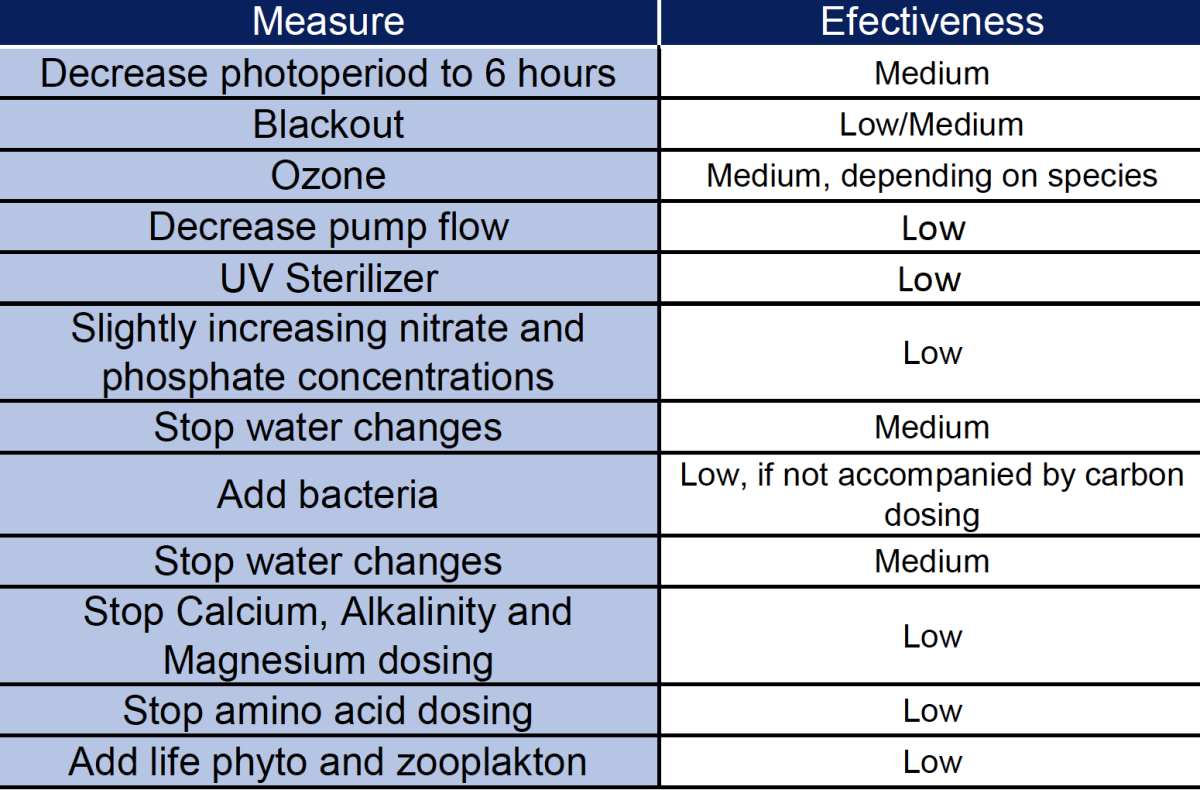

Table 1 shows a list of measures, which alone or in combination, are commonly used by aquarists facing this problem. The table indicate the effectiveness, to the best of my knowledge and experience, of each of them. As we can see, none of the measures have a high degree of effectiveness in all cases, being necessary several of them, and a lot of patience, to reach a successful conclusion.

Table 1. Common measures to fight dinos.

Fortunately, as we will see throughout this article, we have been able to verify that the gradual addition of an external source of organic carbon has a great effectiveness in solving the problem, most likely for all species of dinoflagellates. This treatment has been tested and verified during an experiment conducted in 11 reef aquariums over a period of 7 weeks, in the city of Madrid. In all cases the result has been the eradication of the pest. Let's see the details.

DINOFLAGELLATES. ¿WHAT ARE?

Dinoflagellates are small unicellular organisms belonging to the group of protists, which cannot be categorized as neither animals nor plants, since they have characteristics of both. They move by means of a rotary motion, using their flagella to propel themselves. For example, the well-known zooxanthellae that house corals, anemones and giant clams, are dinoflagellate protists, although they have given up their extensive mobility to have a safe environment within the tissues their host, sheltered from predators

Unwanted dinoflagellates in the aquarium are often are often classified as "algae" because they are photosynthetic protists, although many are mixotrophic organisms, capable of feeding also on simple organic matter. This dual feeding strategy contributes to their great capacity for survival. Many of them release very potent toxins into the water, e.g., Ostreopsis, Gambierdiscus and Prorocentrum species, which generate compounds similar to the palytoxins produced by Zoanthids. As an example, I will describe the life cycle of Osteropsis to understand what we are dealing with.

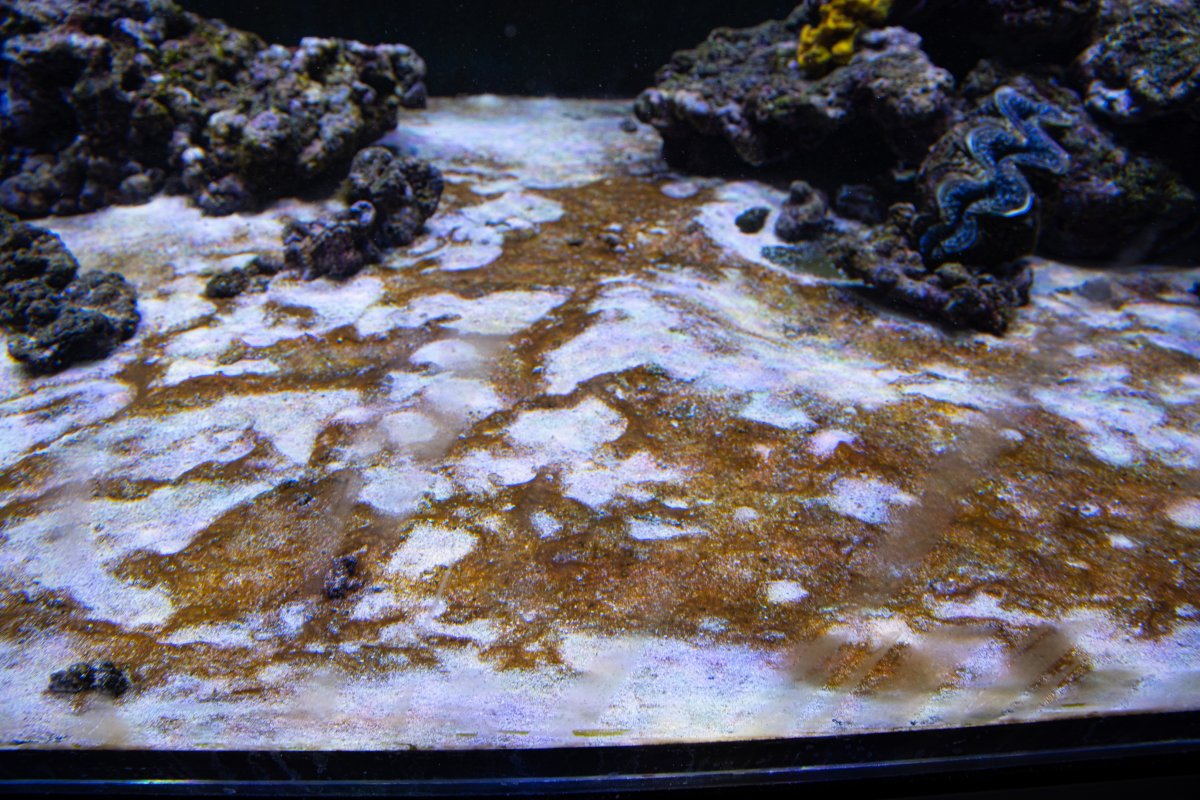

The cells of Osteropsis ovata have a diameter at their largest part, about 40 micro meters, which, if we compare it to the diameter of a cyanobacteria cell (2-3 micro meters), gives us an idea of its relative size. Ostreopsis, like many other harmful dinoflagellates, secretes a large amount of mucus to build extracellular matrices, macroscopically characterized by the presence of strands and filaments, in which oxygen bubbles resulting from photosynthesis are trapped. These matrices settle on any existing substrate, sand, rocks, glasses, etc., suffocating the existing micro fauna.This can be observed, for example, when the aggregates formed on the substratum are siphoned off, revealing areas of sand with a dark gray color, indicating anaerobic bacterial activity, resulting from the depletion of oxygen produced by the layer of dinoflagellates settled on top. The extracellular matrices also serve to immobilize potential predators such as amphipods and copepods.

Ostreopsis and other noxious dinoflagellates have a life cycle characterized by the presence of cysts or resistance forms, which are formed as a result of the union of gametes, although also derived from asexual reproduction. When environmental conditions are not appropriate, for example, a shortage of nutrients or light, these cysts anchor to the substrate and remain "dormant" for months, until the situation improves.

This implies that when we use live rock in the aquarium, we are introducing these cysts as part of the resident micro fauna. It is important to note that the use of inert rock does not prevent the propagation of dinoflagellates, which are unintentionally introduced with the coral frags. In fact, aquaria started with inert rock are noted for a higher incidence and duration of this type of pests, because the lack of microorganism competition. I have been able to verify this point through microscope specimens and interviews with hobbyists. As an example, Figure 1 shows the progression of a dinoflagellate pests in an aquarium set up with 50% inert rock (left) and 50% live rock (right). The difference is remarkable.

Figure 1. Progression of a dinoflagellate pest depending of life rock (right) or inert rock (left)

In the ocean, dinoflagellates produce toxic tides coinciding with periods of rising temperatures and dissolved inorganic nutrients. These blooms, are initiated when the cysts are activated and begin to divide, each cell generating two new individuals and so on. This reproduction generates an exponential pattern that subsequently stabilizes into a flat pattern. After several weeks the population density decreases until the bloom subsides. In the aquarium, the pest behaves in the same way, and can last for months.

DINOFLAGELLATES IN THE REEF AQUARIUM

Dinoflagellates are present in almost all aquaria, forming part of the food web and, therefore, contributing to the general mechanism of nutrient recycling, as they consume light, CO2, nitrate, phosphate, trace elements and dissolved organic matter. If the resident population is limited to a few small colonies and cysts, it does not pose much of a problem. However, it is absolutely necessary to avoid conditions that may favor a bloom, since, once started, it is quite difficult to control and eradicate.

The most favorable scenario is related to young aquaria with very low nitrate and phosphate concentrations, for example, below 0.02 phosphate and 2 ppm nitrate. There is also some probability that a bloom will be triggered when there is a fast reduction in phosphate concentration, which can happen, for example, after the use of lanthanum chloride or GFO. In all aquaria it is good practice to maintain a balanced equilibrium between the two nutrients.

So why, when there is too little nitrate and phosphate in the water, or there is a sudden reduction, is there a greater likelihood of triggering the pest? The answer is neither simple nor immediate, but there are some evidences that help us understand the problem. The key is not in the dinoflagellate itself, since a reduction in the concentrations of nutrients, both organic and inorganic, is not at all favorable to them. What happens is that other competing species, which, among other things, use nitrate and phosphate for food, get starved, and dinoflagellates take advantage of them.

BALANCE, MATURITY AND BIOLOGICAL NICHE

All microorganisms living in a reef aquarium, whether they are bacteria, protists (dinoflagellates, ciliates, coccolithophores, foraminifera, radiolarians), phytoplankton (diatoms, cyanobacteria) or zooplankton (amphipods, copepods) are in continuous competition for light, space or nutrients. They all exchange nutrients with the water. Each organism has a place where it spends most of its day, where it inhabits and performs its main primary functions: feeding, grow and reproduce. Every square cm of a marine aquarium is occupied by an infinite number of these tiny organisms, living in a constant equilibrium. This is what called a biological niche.

When the aquarium reaches a significant maturity (as a reference around 1 year after set-up), the stability of its environmental factors (light, water chemistry, nutrient flow, etc.), favors biodiversity in the populations of all microscopic species, since the greater the stability, the better the conditions for diversity. In this scenario it is more unlikely that one species to dominate over the rest and generate a pest, as most of them have everything they need.

However, when a change occurs, the desired stability is disturbed. The organisms that used to occupy a niche may disappear, die, or simply migrate to find a better place. It is then that the "gap" they leave behind is quickly colonized by other opportunistic and fast-moving organisms. This is the case of unwanted dinoflagellates.

COMPETITION BETWEEN BACTERIA AND DINOFLAGELLATES. THE SURPRISING KEY TO THE SOLUTION.

As we can see, it is practically impossible to eliminate the existence of the different unwanted dinoflagellates in a reef aquarium, since they are introduced with the live rock, invertebrates or frags. The optimal situation is that their populations are limited through natural competition from other organisms such as phytoplankton, zooplankton, or bacteria. As is well known, one of the strategies used to eradicate a dinoflagellate pest caused by maintaining low nitrate and phosphate concentrations is precisely to increase those concentrations. However, the dinoflagellate uses nitrate and phosphate for feeding, so increasing these concentrations will favor it as well.

The rationale for this measure is that the new availability of nutrients will also favor competing organisms, being able to displace dinoflagellates. This strategy is colloquially referred to as "dirty warfare" and its rate of effectiveness is quite low, often favoring the expansion of other unwanted algae such as cyanobacteria or hair algae. However, this mechanism of feeding competing organisms works remarkably well with heterotrophic bacteria. These bacteria aggregate in biofilms within the aquarium substrate, on rocks and other available surfaces, feeding on organic carbon, nitrate, phosphate and trace elements.

It is important to note that all reef aquaria are usually limited in the amount of dissolved organic carbon available to bacteria (DOC), so such bacteria do not grow well until we provide an external carbon source. When adding organic carbon artificially, we get the heterotrophic bacterial communities to displace dinoflagellates.

As simple as this, the reader may ask? The answer is YES.

And why aren't hobbyists using this technique as a pest remediation? The answer is, as in many other cases, fear. The fear comes from the recommendation that all hobbyists follow not to let nitrate and phosphate concentrations fall to undetectable levels, precisely to avoid the risk of cyanobacteria and dinoflagellates blooms. However, in this essay we have verified that, when such low concentrations are the result of the gradual addition of organic carbon, there is no risk of dinoflagellate blooms, but rather, on the contrary, there is a significant regression of the of the existing population, until it disappears completely. As the reader can see, this treatment goes against all recommendations, but it works remarkably. Anyway, it is important to highlight that the risk of cyanobacteria bloom is still there, so we shall not let the inorganic nutrient concentration be reduced too much.

THE TREATMENT

Two brands of organic carbon additives were used in the study Xepta NP out and Red Sea NO3 : PO4-X. After some weeks we got to the conclusion of Xepta being faster in producing the dinoflagellates regression. Xepta NP out is composed of methanol, toluene, glucose, and acetic acid, while Red Sea NO3 : PO4-X contains methanol, ethanol and acetic acid. In the 11 aquaria where this treatment has been applied, the dinoflagellates have receded significantly with either Xepta or Red Sea.

The initial dosage was 1 ml of organic carbon per 100 liters of aquarium water, increasing to an additional 1ml/100 liter per week in cases where dinoflagellates are slow to recede. Up to 3 ml/100 liters have been used in some aquariums. It is important to perform the dosage when the aquarium lights have been turned off, in this way we avoid that the dinoflagellates from taking advantage of the organic carbon. Dose shall not exceed 3 ml/100 l of aquarium water, as we have not tested beyond.

Any sudden excess of organic carbon in aquarium water alters the equilibrium of the coral holobiont, as the heterotrophic bacteria that live within the coral tissues, receive an abnormal dose of food, which can be detrimental to the coral. It is very important that the dosage be as gradually as possible and, at any negative sign in fish, corals and invertebrates, reduce the dosage to half, maintain the treatment, and then increase it again some days after, once the aquarium has self-regulated.

Some side effects detected during the study are depicted below:

- Some corals and tridacnas that have closed more than usual.

- Cloudy water due to bacterial bloom and excessive growth of biofilms inside the return pump pipes.

- Increased export rate from the skimmer. Mostly bacterio plankton and remains of dead organisms.

For cases where there is a large number of dinoflagellates, prior to start the treatment, it is convenient to siphon them out without water change. To do this, a sock is used to retain the dinoflagellates while the siphoned water is returned to the sump. As a consequence of the addition of organic carbon, nitrate and phosphate concentrations will drop significantly, even to the point of being undetectable. We do not want this to happened, because organic carbon addition favors the growth of unwanted cyanobacteria.

ACTION MECHANIMS

The biological mechanism underlying is the combined effect of two factors that cause the dinoflagellate populations to be reduced.

1- Bacteria "steal" food from the dinoflagellates. Due to the addition of organic carbon, the heterotrophic bacteria that are housed in the sand, the rocks and other surfaces of the aquarium, start to reproduce in an extraordinary way, removing nitrate, phosphate and trace elements from the water. They form biofilms that spread on all available surfaces, displacing dinoflagellates.

2- Bacteria directly inhibit the growth of dinoflagellate cells through allelopathy (chemical warfare). The survival strategy of bacteria, protists and phytoplankton, includes a line of defense, which consists of releasing chemical compounds toxic to other species. For example, as a result of copepod predation on diatoms, the algae produce polyunsaturated aldehydes (PUAS), which are noxious to copepods and some phytoplankton species, such as urchin larvae. These PUAS are also produced by other phytoplankton species, such as cyanobacteria, cryptophytes, primnesiophytes, and synurophytes. In addition, PUAS have a potent inhibitory effect on the growth of the dinoflagellate Ostreopsis ovata, altering its DNA structure and disrupting its development.

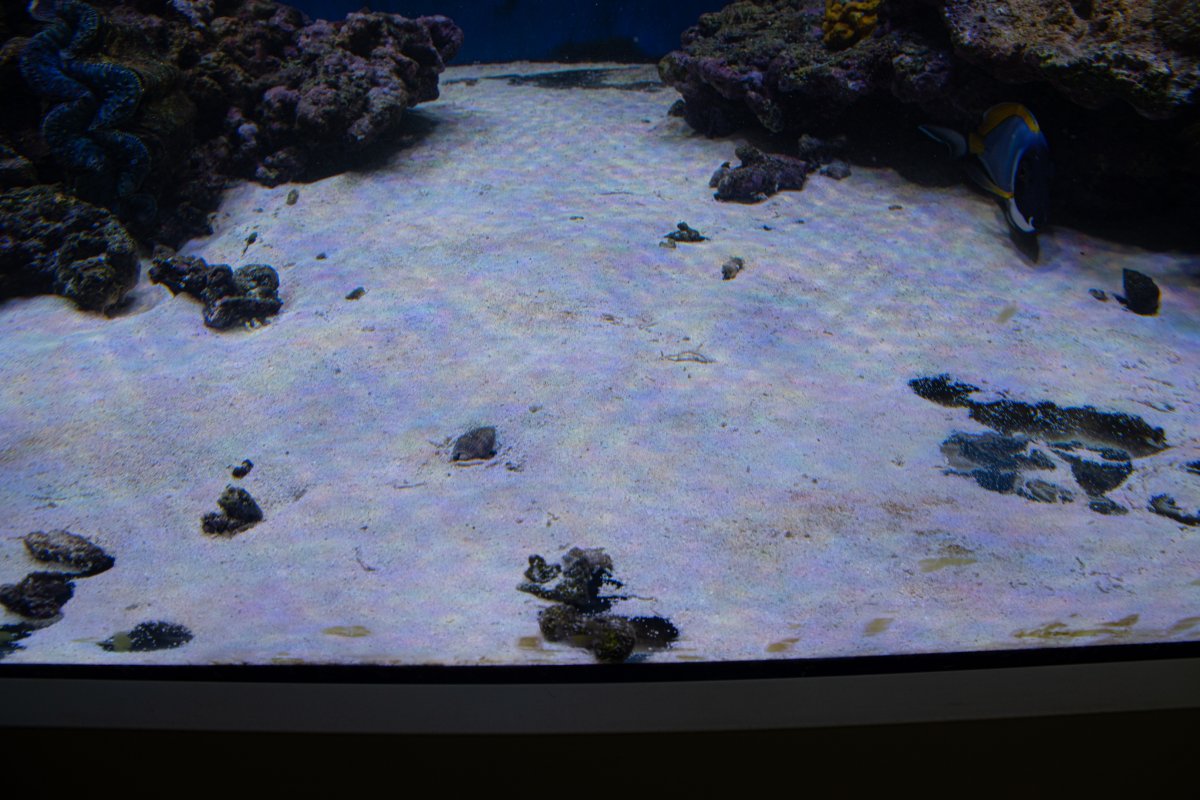

Figures 2 to show the evolution of 2 of the of the 11 aquaria where the essay was carried out. The addition of organic carbon, allows the heterotrophic bacterial communities to reproduce and generate their allelopathy compounds, which inhibit the growth of dinoflagellates. In the following scientific study: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2015.00100/full, it is explained how the dinoflagellate Alexandrium tamarense is inhibited by allelopathy compounds generated by marine bacteria Brevibacterium, Thalassobius, Alteromonoas, Rhodobacteracea, Pseudoalteromonas, Vibrio and Halomonas. According to the article, there is a regression of the cells of Alexandrium tamarense after 10 min, 30 min and 24 h, because of the introduction of the bacteria. The aforementioned study has been kindly shared by Postdoctoral Researcher. Mrs. Esther Garcés, who is a scientific authority in the field of dinoflagellates.

Aquarium no. 1.

Aquarium no. 2.

.

.

.

We can see, therefore, that many organisms are capable of interfering with the growth of others through competition for space and nutrients, but also directly through allelopathy. In an aquarium, where the volume is so extraordinarily limited compared to nature, these chemical warfare compounds are of decisive importance. For example, soft corals emit steroids, diterpenes and sesquiterpenes. which are poisonous to many animals, including hard corals. Anemones also make use of allelopathy in the aquarium, which is proven when, after the introduction of new specimens, resident anemones that were thriving without major problems, begin to undergo swelling cycles, that sometimes lead to their death.

CONCLUSIONS

In the aquarium water, when there is a shortage of, whether nitrate, phosphate, trace elements or organic matter, many of the organisms in the food web, will not be able to complete their metabolic processes and, therefore, to emit their allelopathic compounds or even compete for light and space. This is the perfect scenario for dinoflagellates to spread, as they will not be inhibited by allelopathic compounds and have the capability of growing with ultra-low nutrient concentrations. Dinoflagellates begin to reproduce and spread over all available surfaces, using their flagella, with extraordinary mobility.

Using an external source of organic carbon, heterotrophic bacteria reproduce in an exponential rate, grouping together in biofilms that cover all available surfaces: sand, rocks, pumps, aquarium and sump walls, etc. These biofilms "suffocate" and "intoxicate" dinoflagellates, conveniently deactivating them.

One of the most important conclusions of the test carried out in the 11 aquariums is the following: maintaining very low or undetectable concentrations of nitrate and phosphate in a reef tank, does not pose a risk for the emergence of dinoflagellates, as long as it is a consequence of the addition of an external source of organic carbon. It is important to highlight that the risk of cyanobacteria is still there, as they are favored by organic carbon and not affected by the chemical warfare compounds released by the heterotrophic bacteria.

My recommendation is to always maintain detectable concentrations of both nitrate and phosphate, so that there is a small amount of "leftover" nutrients available for all the organisms, avoiding the growth limitation due to lack of nutrients. During the dosing of organic carbon, it is very important to go progressively, monitoring the status of fish and corals to stop or decrease the dosage at any negative sign. It is necessary to be attentive to fish breathing, water cloudiness and possible symptoms of STN in corals.

Yes, but it will need adjustment as there will be an increase in the skimmedVery nice investigation. While using the Xepta NP, should my skimmer remain on through out the reduction process?

- Joined

- Mar 10, 2018

- Messages

- 98

- Reaction score

- 60

Thank you!Yes, but it will need adjustment as there will be an increase in the skimmed

I am having great difficulty finding a place that sells Xepta NP Out. Any suggestions?Very nice investigation. While using the Xepta NP, should my skimmer remain on through out the reduction process?

I am having great difficulty finding a place that sells Xepta NP Out. Any suggestions?Yes, but it will need adjustment as there will be an increase in the skimmed

Thank you, great write up! I dose carbon and the single thing you stated that "turned the light bulb on" was dosing it in the dark. I never considered the fact that the very issues we are trying to control would also make use of the carbon during the their photosynthetic process! Just started my daily carbon dosing early AM, 4 hours before the lights will come on. Thanks again!

HI Karliefish, you can try with the traditional vodka, vinegar and sugar recipe:KerI am having great difficulty finding a place that sells Xepta NP Out. Any suggestions?

225 ml of vodka (40%)

25 ml of white vinegar

1 tea spoon of brown sugar

Dose is 0,5 ml/100 liters of aquarium water per day, fist week and increase 1 ml per week

Yes, I believe it is better to dose in complete darkness, so when there is the peak in the organic carbon concentration the dino is supposed unable to take a significante advantage of it, assuming the carbon dosing uptake is higher during the light period. A Spanish hobbyist reported an huge improvement when the blue moon was switched of...Thank you, great write up! I dose carbon and the single thing you stated that "turned the light bulb on" was dosing it in the dark. I never considered the fact that the very issues we are trying to control would also make use of the carbon during the their photosynthetic process! Just started my daily carbon dosing early AM, 4 hours before the lights will come on. Thanks again!

Hi,

There are two guys here reporting ammonia reading during the organic carbon treatment at high doses, or when increasing too quick. Anyone?

There are two guys here reporting ammonia reading during the organic carbon treatment at high doses, or when increasing too quick. Anyone?

- Joined

- Aug 24, 2016

- Messages

- 368

- Reaction score

- 438

I feel like dinos didnt use to be a problem and then they exploded the last like 6 years with everyone getting refugiums and massive protein skimmers effectively nuking nutrients and phosphates.This thread is for the general discussion of the Article Dinoflagelates. A disruptive treatment. Please add to the discussion here.

I have tried that in the past and it did a great job in managing Nitrate & Phosphates. I didn’t know that method of dosing method was good for eliminating Dinos. Did you have success with this carbon dosing method?HI Karliefish, you can try with the traditional vodka, vinegar and sugar recipe:

225 ml of vodka (40%)

25 ml of white vinegar

1 tea spoon of brown sugar

Dose is 0,5 ml/100 liters of aquarium water per day, fist week and increase 1 ml per week

My apologies…..I wasn’t clear in my comment. The article highlights how effective Xpeta NP Out was at eliminating dinos. I was trying to under if the traditional vodka method was as effective. I thought I read in the article that the elements contained in Xpeta made it more effective at eliminating dinos.Yes, this post is all about that. Please kindly check the article

Similar threads

- Replies

- 2

- Views

- 193

- AMS: Article

- Replies

- 1

- Views

- 52

- Replies

- 6

- Views

- 377

- Replies

- 23

- Views

- 957