As coral famers, importers, and handlers we get to see a lot of different corals on a daily basis. We care for thousands of specimens of hundreds of species at one time. And that's not only a recipe for occasional trouble- it's a good way to learn a few things about coral care! We have made plenty of mistakes, but we've also learned from them, and today, I'll offer you a few tidbits that we've learned from hard experience that might whelp you in your coral husbandry efforts.

Perhaps your corals just aren't looking quite like they used to. Colors and behaviors are off, etc. What are the signs? What do they mean? What was the cause, and what can you do to to correct the problem? Here are some of the more common issues we've run into and our observations on each:

The polyps don’t extend like they used to- Well, this is definitely a sign that something might be amiss…Coral polyps are used for feeding, and an animal that doesn’t feed….well, you get the picture. The root cause of this, in our experience, always seems to be some sort of environmental parameter swing, such as temperature or alkalinity.

If it used to be "hairy", and it isn't, something's up.

It’s a common theme in coral care, but the importance of stable environmental parameters just can’t be stressed enough. It’s not about specific numbers- it’s more about keeping the numbers within a certain range.(NOTE: Soft corals, such as Sarcophyton, will often retract their polyps for extended periods of time to shed a waxy mucuus coat. This is considered a normal part of the coral’s life processes. Once the “shedding†is complete, the polyps will re-emerge.). Another, often overlooked cause of this "retracting" phenomenon, seems to be flow…In our case, it was just too darned much in some instances. Our advanced, uber-cool “stealth†gyre flow systems, designed by Jake Adams, provide wicked flow at minimal power expenditure, and flow is of vital importance to coral health.

Some corals, like this Sarcophyton, will retract their polyps from time to time as part of their normal life processes.

Although I won’t go into the specifics of our systems’ flow design (the general information is out there in Jake’s writings, but the engineering aspects and physics of our particular setups will remain under wraps for now - gotta keep some things proprietary…we’ve seen other vendors attempt to duplicate our system, with varying degrees of success, I might add…So we enjoy our advantage there!), suffice it to say that, as Jake likes to say- flow is perhaps more important than light. However, some coral don’t do well under super high flow. Our solution was to create some physical flow “speedbumps†and to learn our systems to see where the areas of slightly less flow were, and place corals carefully based on their specific flow requirements. When we make flow recommendations on our coral pages, they aren’t just pulled from “the booksâ€- they are based on our actual experience.

Wicked flow is good...usually.

The coral’s color is not what it used to be, or SHOULD be. We’ve all seen this before, right? The once vibrant tissue is pallid and washed-out. In our experience, this condition is generally caused by one thing: The water is just too darned…well, clean! Yeah, we’ve talked about this here before, right? We kept our raceways so **** clean, you could literally give birth in them. And you know what? Our corals colors were just not there. We tested for everything- we had undetectable nitrate, phosphate, etc….Then we looked at some of our personal system where corals were displaying vibrant colors and thriving. What was the common theme? Measurable, but low nitrate, phosphate, and large, well-fed fish populations.

So, we added more fishes, like tangs, wrasses, etc to our raceways- and fed them. A lot. As a result, they poop a lot, right? Good for corals! We shut off the water flow and fed our corals when they wanted to be fed- in the dark, with feeding polyps extended. We started using “Acro Power†amino acids from Julian Spring’s Two Little Fishies on a regular basis, along with Potassium. We just plain relaxed a bit. We even stopped using the protein skimmers in our raceways every single day…this, in my opinion, always amounted to heresy. But guess what? Colors began to return, the corals grew faster, and they looked amazing. We still monitor water quality several times a week…but we look for trends, rather than obsess over target numbers. Are you sensing a theme here? Good. We get dozens of emails a week and lots of great comments from our customers about how vibrant and healthy our corals are. We must be doing something right, huh?

Our finned friends help our corals in lots of ways...don't leave them out of your coral tanks!

The tissue at the base of the coral is bleached out, or areas at different parts of the coral appear to be bleached. On stony corals, such as Acropora, Stylophora, etc. this is often caused by things like stress from shipping, lapses in environmental conditions, particularly alkalinity or temperature swings. We saw this phenomenon early on in our facility’s existence, when we couldn’t quote manage to keep these particular environmental parameters tight. This is a bit different than “RTN†or “STNâ€. This is a simple “bleaching†of random areas of the coral.

Once we were able to keep our systems more stable (ie; minimize or eliminate alkalinity and temperature swings), this became a thing of the past. Of course, you might see whitening of the tips or branches periodically because of some repeated physical insult, such as the coral being damaged ( ie; coming in contact with a more aggressive coral, being scraped by a fish or invert, etc.), or less frequently, a pest like flatworms, etc.

The takeaway here is to keep things a) stable within a range, b) from bumping into each other or otherwise coming into direct physical contact with each other, and c) inspect for pests regularly. We even noticed this phenomenon when we went through a period when we were overly obsessed about dipping our corals for pests. When we relaxed a bit, and followed more relaxed protocols, this problem subsided. Above all, don't panic! Just asks yourself questions and work the problem without adding to it.

Other things we’ve noticed: Some corals just don’t respond well to fragging. Period. For example, our beloved “Strawberry Shortcakeâ€, Acroproa microclados, just flat-out looks like crap after its fragged. There is a very long delay from the time the mother colonies are fragged until the time when the frags are actually marketable. It takes a month or more to make a frag that anyone would recognize as a “Shortcakeâ€, let alone, want to purchase. The frags almost always go brown within days after being fragged, then slowly, over a period of weeks, they encrust at the base, and gain some pink, then ultimately, yellow.

To get a "Shortcake" this tasty, you just can't rush things!

So when you see super bright “Strawberry Shortcakes†on clean plugs without being encrusted at all, it’s almost a guarantee that you’re looking at a fresh cut frag that will usually go south quickly before it comes back. I'm not being negative here. Just offering a friendly warning from the folks who actually “named†this popular morph and have worked with it for a long time. Other corals, such as Acroproa spathulata and, to a lesser degree, Acropora valida and Acropora millepora, will also display this “ugly duckling†phenomenon with some degree of regularity. You just can’t hurry love, as they say.

Some corals don't travel well, either. Like people, some corals just don’t like getting on airplanes. They’d rather be left alone in their raceways, unmolested and undisturbed. Chalices and Acans are prime examples. Often, they will take days, or sometimes even weeks, to regain their ultimate colors again after being shipped to a customer. They seem to require inordinately long acclimation periods in some instances. Fortunately, the majority of the corals that we work with ship quite well, and acclimate easily to new surroundings. In fact, even the Chalices and Acans acclimate well, they just take a bit longer to attain their former glory in many instances. The key as a consumer, is not to panic and start moving them all over the tank and messing with them if they don’t look perfect on arrival..Just give them some time and care, and they’ll be there!

Ok, so there you a a few of the common reasons why corals just don’t look right, and what to do about them. None of this is proprietary, absolute gospel, rocket science, or even revolutionary. It’s pretty basic stuff. However, this little offering is based on our personal experiences, trials, and tribulations, and perhaps you might use this information as either a starting point or validation for your own observations and husbandry techniques. Sometimes it's nice to see what someone else is doing. You'll realize that we all face the same challenges, and everyone's experiences are helpful! For everything that we do know about coral care, there is so much that we don’t know!

Let’s hear a little about your personal observations, experiences, tricks, and ideas about keeping your amazing corals well…amazing! Don't be shy- every observation is important...Share!

Thanks again for stopping by, and as always…

Stay Wet.

Regards,

Scott Fellman

Unique Corals

Perhaps your corals just aren't looking quite like they used to. Colors and behaviors are off, etc. What are the signs? What do they mean? What was the cause, and what can you do to to correct the problem? Here are some of the more common issues we've run into and our observations on each:

The polyps don’t extend like they used to- Well, this is definitely a sign that something might be amiss…Coral polyps are used for feeding, and an animal that doesn’t feed….well, you get the picture. The root cause of this, in our experience, always seems to be some sort of environmental parameter swing, such as temperature or alkalinity.

If it used to be "hairy", and it isn't, something's up.

It’s a common theme in coral care, but the importance of stable environmental parameters just can’t be stressed enough. It’s not about specific numbers- it’s more about keeping the numbers within a certain range.(NOTE: Soft corals, such as Sarcophyton, will often retract their polyps for extended periods of time to shed a waxy mucuus coat. This is considered a normal part of the coral’s life processes. Once the “shedding†is complete, the polyps will re-emerge.). Another, often overlooked cause of this "retracting" phenomenon, seems to be flow…In our case, it was just too darned much in some instances. Our advanced, uber-cool “stealth†gyre flow systems, designed by Jake Adams, provide wicked flow at minimal power expenditure, and flow is of vital importance to coral health.

Some corals, like this Sarcophyton, will retract their polyps from time to time as part of their normal life processes.

Although I won’t go into the specifics of our systems’ flow design (the general information is out there in Jake’s writings, but the engineering aspects and physics of our particular setups will remain under wraps for now - gotta keep some things proprietary…we’ve seen other vendors attempt to duplicate our system, with varying degrees of success, I might add…So we enjoy our advantage there!), suffice it to say that, as Jake likes to say- flow is perhaps more important than light. However, some coral don’t do well under super high flow. Our solution was to create some physical flow “speedbumps†and to learn our systems to see where the areas of slightly less flow were, and place corals carefully based on their specific flow requirements. When we make flow recommendations on our coral pages, they aren’t just pulled from “the booksâ€- they are based on our actual experience.

Wicked flow is good...usually.

The coral’s color is not what it used to be, or SHOULD be. We’ve all seen this before, right? The once vibrant tissue is pallid and washed-out. In our experience, this condition is generally caused by one thing: The water is just too darned…well, clean! Yeah, we’ve talked about this here before, right? We kept our raceways so **** clean, you could literally give birth in them. And you know what? Our corals colors were just not there. We tested for everything- we had undetectable nitrate, phosphate, etc….Then we looked at some of our personal system where corals were displaying vibrant colors and thriving. What was the common theme? Measurable, but low nitrate, phosphate, and large, well-fed fish populations.

So, we added more fishes, like tangs, wrasses, etc to our raceways- and fed them. A lot. As a result, they poop a lot, right? Good for corals! We shut off the water flow and fed our corals when they wanted to be fed- in the dark, with feeding polyps extended. We started using “Acro Power†amino acids from Julian Spring’s Two Little Fishies on a regular basis, along with Potassium. We just plain relaxed a bit. We even stopped using the protein skimmers in our raceways every single day…this, in my opinion, always amounted to heresy. But guess what? Colors began to return, the corals grew faster, and they looked amazing. We still monitor water quality several times a week…but we look for trends, rather than obsess over target numbers. Are you sensing a theme here? Good. We get dozens of emails a week and lots of great comments from our customers about how vibrant and healthy our corals are. We must be doing something right, huh?

Our finned friends help our corals in lots of ways...don't leave them out of your coral tanks!

The tissue at the base of the coral is bleached out, or areas at different parts of the coral appear to be bleached. On stony corals, such as Acropora, Stylophora, etc. this is often caused by things like stress from shipping, lapses in environmental conditions, particularly alkalinity or temperature swings. We saw this phenomenon early on in our facility’s existence, when we couldn’t quote manage to keep these particular environmental parameters tight. This is a bit different than “RTN†or “STNâ€. This is a simple “bleaching†of random areas of the coral.

Once we were able to keep our systems more stable (ie; minimize or eliminate alkalinity and temperature swings), this became a thing of the past. Of course, you might see whitening of the tips or branches periodically because of some repeated physical insult, such as the coral being damaged ( ie; coming in contact with a more aggressive coral, being scraped by a fish or invert, etc.), or less frequently, a pest like flatworms, etc.

The takeaway here is to keep things a) stable within a range, b) from bumping into each other or otherwise coming into direct physical contact with each other, and c) inspect for pests regularly. We even noticed this phenomenon when we went through a period when we were overly obsessed about dipping our corals for pests. When we relaxed a bit, and followed more relaxed protocols, this problem subsided. Above all, don't panic! Just asks yourself questions and work the problem without adding to it.

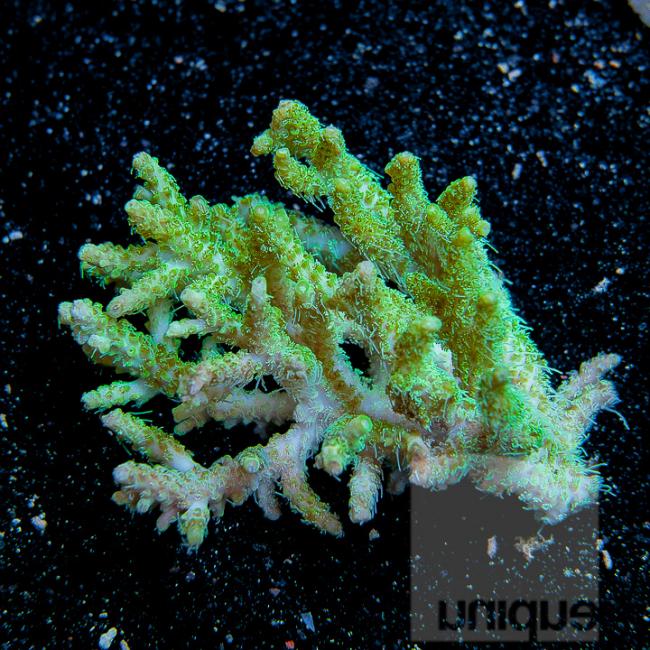

Other things we’ve noticed: Some corals just don’t respond well to fragging. Period. For example, our beloved “Strawberry Shortcakeâ€, Acroproa microclados, just flat-out looks like crap after its fragged. There is a very long delay from the time the mother colonies are fragged until the time when the frags are actually marketable. It takes a month or more to make a frag that anyone would recognize as a “Shortcakeâ€, let alone, want to purchase. The frags almost always go brown within days after being fragged, then slowly, over a period of weeks, they encrust at the base, and gain some pink, then ultimately, yellow.

To get a "Shortcake" this tasty, you just can't rush things!

So when you see super bright “Strawberry Shortcakes†on clean plugs without being encrusted at all, it’s almost a guarantee that you’re looking at a fresh cut frag that will usually go south quickly before it comes back. I'm not being negative here. Just offering a friendly warning from the folks who actually “named†this popular morph and have worked with it for a long time. Other corals, such as Acroproa spathulata and, to a lesser degree, Acropora valida and Acropora millepora, will also display this “ugly duckling†phenomenon with some degree of regularity. You just can’t hurry love, as they say.

Some corals don't travel well, either. Like people, some corals just don’t like getting on airplanes. They’d rather be left alone in their raceways, unmolested and undisturbed. Chalices and Acans are prime examples. Often, they will take days, or sometimes even weeks, to regain their ultimate colors again after being shipped to a customer. They seem to require inordinately long acclimation periods in some instances. Fortunately, the majority of the corals that we work with ship quite well, and acclimate easily to new surroundings. In fact, even the Chalices and Acans acclimate well, they just take a bit longer to attain their former glory in many instances. The key as a consumer, is not to panic and start moving them all over the tank and messing with them if they don’t look perfect on arrival..Just give them some time and care, and they’ll be there!

Ok, so there you a a few of the common reasons why corals just don’t look right, and what to do about them. None of this is proprietary, absolute gospel, rocket science, or even revolutionary. It’s pretty basic stuff. However, this little offering is based on our personal experiences, trials, and tribulations, and perhaps you might use this information as either a starting point or validation for your own observations and husbandry techniques. Sometimes it's nice to see what someone else is doing. You'll realize that we all face the same challenges, and everyone's experiences are helpful! For everything that we do know about coral care, there is so much that we don’t know!

Let’s hear a little about your personal observations, experiences, tricks, and ideas about keeping your amazing corals well…amazing! Don't be shy- every observation is important...Share!

Thanks again for stopping by, and as always…

Stay Wet.

Regards,

Scott Fellman

Unique Corals