MISSION: 2018

I’ve certainly spent enough time talking abstract philosophy of late, right? While I’m pleased with the level of discussion, I think it’s time to talk about ways to run a more biologically diverse reef system in 2018. With all of the cool gear around, to me it’s actually more beneficial to talk about the way I’d want to set up the system- it’s “theme” and philosophy (ahrggh, there’s that word again!).

So, my stated goal is to create a modest-sized aquarium that embraces natural processes which occur in various niches within the reef biome. Now, that being said, I am interested in more of a lagoon-type habitat, preferably one with a strong connection to the nearby land. I am fascinated about the idea of incorporating mud, biosediment, and other substrate materials into the display. The idea of re-creating a little habitat around a mangrove tree and some seagrass, or to attempt to replicate those “coral islands” in Palau (reef below, terrestrial plants above) has been tugging at me for decades…and I think it might be time to play with one of these concepts.

WHAT’S MUD GOT TO DO WITH IT???

Yes, you’ve heard me yammer about it, but I’m still really into the idea of using various types of ocean-sourced muds and sediments in our aquariums. This is not exactly new. It’s something we've played with over the past few decades, right? Yet, with all of the ideas of sandbeds and such, I think we should be utilizing natural mud, or the really great substrates offered by companies like CaribSea, Brightwell, Seachem, etc. And let’s not forget “Miracle Mud”, too! Now, I’m not talking about using these products because of some over-hued marketing hyperbole about them curing sick fishes and raising corals from the dead or whatever. Nope.

I’m curious about the way these materials can impart trace elements into the water. I’m curious how they foster identification. I’m very interested in the possibility of them providing additional foraging opportunities for a wide variety of fishes (specifically fishes like Halichoeres sp. Wrasses, Ctenochaetus sp. Tangs, and Pseduchromids, just to name a very few.). And I’m almost obsessed with the possibility that they can serve as an in-tank refugium (well,sorta) for cultivation of animals which might serve as supplementary food sources for most of the fishes and higher invertebrates in our systems.

Mud was one of those odd tangents that hit right around the “early 2000’s refugium craze, and sort of faded quickly into the background. I am sure that part of it was a renewed obsession later in the decade with less biodiverse, more “coral-centric” systems, which eschewed substrates in general, specifically those which had the tendency to house competing biota! All of those factors- and a continued (and cool, I might add) obsession with using high tech electronic pumps to facilitate ridiculous amounts of water movement within our aquariums sealed the fate of mud as a true reef “side show” for the foreseeable future.

Now here we are, in the fading years of the 2nd decade of the new millennium, and I think that it’s time to resuscitate the idea of using mud in our reef tanks again in some capacity. And I’m thinking not JUST the refugium. I’m talking about the display! Now, I realize that a lot of reefers will disagree with my thinking, and duly advise that sand and mud and sediment can become “nutrient sinks” and work against the smooth operation and long term prosperity of a reef. The operative word here, IMHO- is CAN. I mean, even water exchanges can be problematic if poorly executed, right? So I think it might be worth looking at how a well-managed mud/sediment/sand bed could help support a healthy, diverse closed reef ecosystem.

Now, if you go way back into the past (like 2005), you may recall some of the studies into various substrate depths and compositions (and plenums!) and their relative impact on mortality of animals in aquaria. Now, in all fairness, the test subjects were fishes and inverts like hermit crabs and snails, but the findings are nonetheless relatable, in my opinion, to reef tanks. Tonnen and Wee ran a lot of tests with different depths of substrate, ranging from very dahlia to rather deep, and the results were quite fascinating, in my opinion. Interestingly, one conclusion was that “...the shallower the sediment, the higher the mortality rate, and you can't get much shallower than a bare bottom tank!"

Again, that set of experiments had a lot of different variables, like the aforementioned plenum, as well as the use of pretty coarse substrate in some setups (Not too many of us use that stuff!),and no real test using marine muds and sediments as the sole substrate in a reef setting. However, I think it is perhaps safe to say that the presence of a substrate itself in a reef tank doesn’t spell disaster for the inhabitants- be they fish, corals, or urchins…The reality is that a well-managed, carefully stocked reef tank should work under a variety of situations.

And of course, the cautions are warranted. A poorly maintained sandbed, without some creatures present to stir up the upper layers, can prove problematic if detritus and organic wastes are allowed to accumulate unchecked, right? And there is the so-called “old tank syndrome” (Paul, you’ll have a field day with this, right?) that suggests that after some point in a reef systems operational lifetime (whatever that might be!) the bacteria population within the system (likely the sanded) is depleted somehow and/or no longer has the ability to keep up with the accumulations of organic waster products, and that phosphates and such are released back into the system.

I am probably being a jerk, and simply being biased, but I have a real problem with that theory. I just don’t see how a well-managed aquarium declines over the years. I’ve personally maintained one reef tank for 11 years, and one freshwater tank for 16 years and never had these issues. I’m not saying to nominate me for sainthood or anything, but I will tell you that I am a firm believer in not overstocking my tanks, utilizing multiple nutrient export avenues (protein skimming, activated carbon, use of macro algae/plants, and weekly water exchanges). There is no magic there.

Okay, that being said, tanks with substrate, specifically fine sediment materials like mud and such, are not “set and forget” systems. You’ll need to be actively involved. And by “actively involved”, I mean more than tweaking the lighting settings on your LEDS via your iPhone). You’ll need to get your hands wet. Which to me, is the best part of reef keeping!

Now, I’m literally just scratching the surface here, deliberately not going too deep into this because I’d like your thoughts and input. However, I think it’s absolutely possible to maintain a successful reef system with mud and other marine sediments as a significant part of the substrate. One of the keys, in my opinion, is to utilize some marine plants…you know- seagrasses.

Yep- thats’ a whole different story for another time, but I will touch on them here to open things up more. I think they are deserving of more attention from reefers.

Okay, we all have probably seen or heard about them at one time or another, but rarely do we find ourselves actually playing with them! They are not at all rare in the wild- In fact, they are found all over the world, and there are more than 60 species known to science. Seagrass beds provide amazing benefits to coral reef ecosystems, such as protection from sedimentation, a “nursery” for larval fishes, and a feeding ground for many adult fishes.. In the aquarium, they can perform many of the same functions. So why are we not seeing more of them in the hobby?

I believe there are three main reasons why we don’t: 1) They suffer from what I call the “Caulerpa Syndrome”- a bad rep ascribed to just about anything green in the marine hobby- “They will smother your corals”, or “They can crash and kill everything in the tank”, or even, “They give off toxic byproducts that inhibit coral growth”. 2) There simply aren’t enough people working with them to get them out to the hobby in marketable quantities. 3) They are finicky and hard to grow.

Let’s beat up Number 1 first: Seagrasses are true vascular plants, not macroalgae, and they do not creep over rocks, go “sexual” and crash, or exude chemicals that will stifle the growth of your “True Echinata”! In fact, they are mild-mannered, grow at a relatively modest rate, and are compatible with just about everything we keep in a reef tank. And no, they will not smother your corals or grow over rockwork. They grow in soils and sandbeds, and need to put down root systems. You can keep them nicely confined to just the places that you want them. Dedicate a section of sandbed that you’d like them to grow, plant them, give them good conditions, and you’ll be singing their praises in no time!

Reason Number 2 is probably caused in part by #1, but in actuality, is the most probable reason why we don’t see them everywhere: Until very recently, they were the sole domain of dedicated specialty hobbyists, who delighted in growing plants and taking on other challenges. The hobby as a whole simply never sees them in quantity, helping spur the (false) image that they are rare, dangerous, or difficult to work with. Someone (hey- that can be YOU) needs to step up and produce/distribute them in quantity! (if you don’t…I will, lol)

Reason Number 3 has a bit of truth to it. Some of the seagrasses can be a bit finicky at first, and don’t always take initially when transplanted. Like any plant, they go through an adjustment period, after which they will begin to grow and thrive if conditions are to their liking. It has also been discovered in recent years that there are microbial associations in the soils/sediments that they are found in which enable them to settle in better and adapt to new conditions. So in short, if you are obtaining seagrasses, you can never hurt your cause if they come with some of the substrate that they grew in.

If you can provide a mature, rich sand bed (say 3”-6”), good quality lighting (daylight spectrum or 10k work well), decent water quality, and no large populations of harsh herbivorous fishes, like Tangs or Rabbitfishes), you can almost guarantee some success. And the other key ingredient is patience. You need to leave them alone, let them acclimate, and allow them to grow on their own.

By the way, you can use a variety of commercially-available substrate materials in addition to your fish-waste-filled sand, such as products made by Kent Marine, Seachem and Carib Sea, that are designed just for this purpose! How ironic- products exist to help grow seagrasses, and so few people are actually taking advantage of them! Oh, and wait, a well-stocked reef is capable of creating a good rich sand bed, huh?

There are three main species that we find in the hobby: Halodule, or “Shoal Grass”, Halophilia , knows as “Stargrass”, “Paddle Grass”, or “Oar Grass”, and Thalassia, known commonly as “Turtle Grass”. I call them “The Big Three”. Each one has slightly different requirements, and I will briefly cover them here.

Halodule looks a lot like the freshwater plant Sagittaria, or “Micro Sword”, in my opinion- and grows like it, too. Plant it in a modestly deep (3”), rich substrate, and it will put down a dense system of runners as it establishes itself. Once it establishes itself, it’s about as easy to grow as an aquatic plant can be, IMO. I think it’s the best candidate for extensive captive propagation, so those of you with greenhouses should devote a tray or two to this stuff. I envision this being grown in “pony packs” like you see with groundcover plants at your local nursery, so that a hobbyists can purchase a “flat” of Halodule and simply plop it into their tank.. Think of the commercial possibilities here, folks!

Halophila is a very attractive plant, which, although slightly more delicate and challenging than Halodule, is still relatively easy to grow, and is really pretty, too! I’ve grown this plant in substrates as shallow as 2.5”, but you probably want 3” or more for good solid growth. This seagrass definitely “shocks out” when you transplant it, and you will lose some leaves straight away. However, with patience, good conditions, and a little time, it will come back into its own and form a beautiful addition to your reef tank. And man, it would be a nice sight to see at your next club frag swap- I’ll bet you could get a choice “Superman Monti” in trade for a few Halophila!

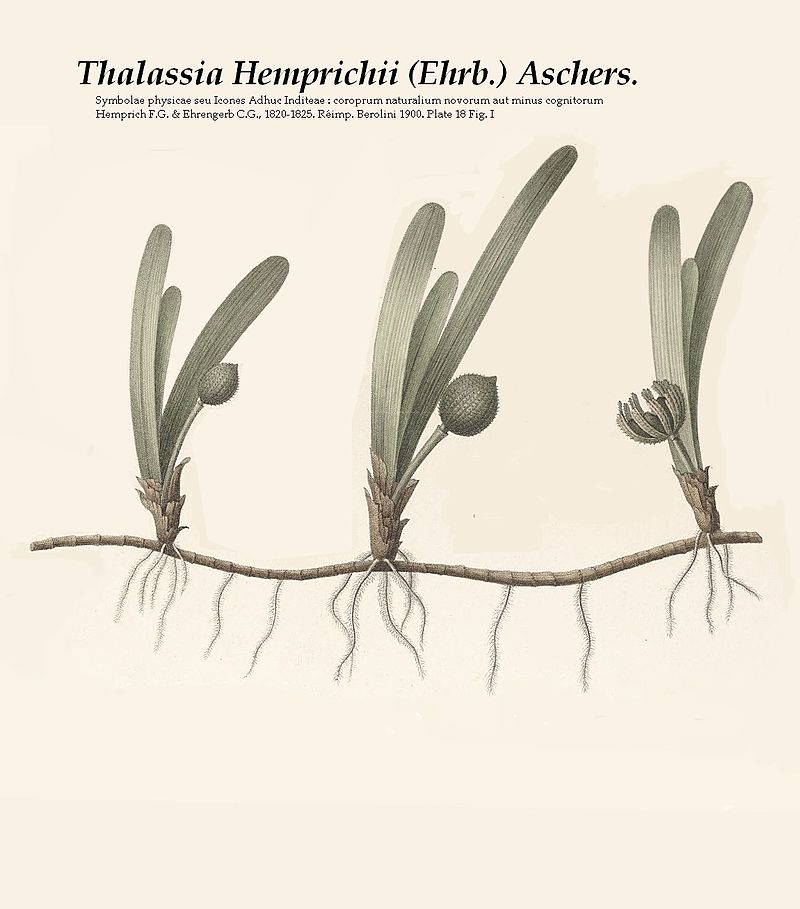

Thalassia is “THE” seagrass to most people- the one we envision when we hear the term “Seagrass”. It’s called “Turtle Grass”, and it is one of the larger varieties, growing up to 24” in height if space permits. Its thick leaves create a beautiful contrast to rockwork, and it can create an interesting area for fishes to forage when you can get a thick growth of it. It does grow VERY slowly, and you will typically have to start with a quite a few plants if you are trying to fill in a designated space in your tank. It requires a pretty deep sandbed, too- 5 to 6 inches or more is ideal. Because of it’s slow growth rate and height requirements, it’s the least attractive candidate for captive propagation, IMO. However, it is still a lovely plant with much to offer.

Seagrasses offer just another interesting diversion and an opportunity for the hobbyists to try something altogether new in the aquarium. Not only will you be growing something cool and exciting, you’ll have a chance to get in on the ground floor of a new area of the marine hobby. By unlocking the secrets of seagrasses, you will be further contributing to the body of knowledge of the husbandry of these plants. Obviously, I just scratched the uppermost surface of the topic here, but I’m hopeful that I have piqued your interest enough to give the seagrasses a try!

Oh, man, was that a tangent, right?

Well, not totally, because it’s my opinion that the key to a high biodiversity reef tank in the long term would be to incorporate these true vascular plants into the mix. And mangroves, too! Now, I would be fooling myself and all of you if I felt that a mangrove pant in your reef is going to contribute in any meaningful way to nutrient export for your system. Sure, they may pull some nutrient from the water or substrate, but their real value, in my opinion, is to foster the growth of epiphytic life (diatoms, tunicates, etc.) which contribute to the nutrient export and biodiversity of the aquarium.

And of course, they look cool. And I am very fascinated about playing with mangroves leaves, and the decomposing materials and how they interplay with the aforementioned sediments, and corals…There’s a lot going on there. It’s a lot to consider for a reef tank…but I can’t help but feel that there is something to be gained by incorporating mangroves into the mix…I have visited Julian Sprung’s unique and highly diverse reef systems several times, and each time I’m taken with just how well everything functions as part of a whole- plants, macroalgae, seagrass, sponges, tunicates, feather dusters, coral, invest…fishes. Real deal diversity. Truly the microcosm that John Tullock outlined so many years ago.

I’m a firm believer that people like Julian, Paul B., and others are successful with their diverse systems long term because they understand and appreciate the biodiversity, and provide conditions which allow the largest majority of life forms to prosper for the longest period of time. Also, the guys have made the “mental shift” that those of you who follow my freshwater writing here me speak of so often…The mental shift that understands and appreciates the way these systems actually look. A POV that realizes that some algae, some detritus, and some nitrate/phosphate is not only inevitable- it’s desirable. It’s a mode of thinking which gets away from the “Coral is everything and the tank must be spotless, with every technical prop used to assure this…” and embraces a mindset of “The tank must be lush and diverse, with a wide variety of animals thriving as they do in nature in a stable environment.”

Two perfectly valid mindsets, with somewhat similar goals, but dramatically different approaches to get there, and viewpoints as to which aesthetic is most attractive. I am not saying that we all need to ditch all of our high tech gear and go back to trickle filters, 5,000k halides, and massive pump-powered protein skimemrs. What I am suggesting is that we utilize the technology and information that is available today and apply it to some of the more interesting approaches from the past which foster more diverse reef systems.

The time has never been more appropriate. Time to look at some of these “niche” ideas with a new mindset- and a new appreciation for what they can accomplish!

Let’s hear your thoughts on some of these approaches and how the best parts might be incorporated into a “second decade” twenty-first century reef tank!

Stay bold. Stay curious. Stay engaged. Stay open-minded…

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

I’ve certainly spent enough time talking abstract philosophy of late, right? While I’m pleased with the level of discussion, I think it’s time to talk about ways to run a more biologically diverse reef system in 2018. With all of the cool gear around, to me it’s actually more beneficial to talk about the way I’d want to set up the system- it’s “theme” and philosophy (ahrggh, there’s that word again!).

So, my stated goal is to create a modest-sized aquarium that embraces natural processes which occur in various niches within the reef biome. Now, that being said, I am interested in more of a lagoon-type habitat, preferably one with a strong connection to the nearby land. I am fascinated about the idea of incorporating mud, biosediment, and other substrate materials into the display. The idea of re-creating a little habitat around a mangrove tree and some seagrass, or to attempt to replicate those “coral islands” in Palau (reef below, terrestrial plants above) has been tugging at me for decades…and I think it might be time to play with one of these concepts.

WHAT’S MUD GOT TO DO WITH IT???

Yes, you’ve heard me yammer about it, but I’m still really into the idea of using various types of ocean-sourced muds and sediments in our aquariums. This is not exactly new. It’s something we've played with over the past few decades, right? Yet, with all of the ideas of sandbeds and such, I think we should be utilizing natural mud, or the really great substrates offered by companies like CaribSea, Brightwell, Seachem, etc. And let’s not forget “Miracle Mud”, too! Now, I’m not talking about using these products because of some over-hued marketing hyperbole about them curing sick fishes and raising corals from the dead or whatever. Nope.

I’m curious about the way these materials can impart trace elements into the water. I’m curious how they foster identification. I’m very interested in the possibility of them providing additional foraging opportunities for a wide variety of fishes (specifically fishes like Halichoeres sp. Wrasses, Ctenochaetus sp. Tangs, and Pseduchromids, just to name a very few.). And I’m almost obsessed with the possibility that they can serve as an in-tank refugium (well,sorta) for cultivation of animals which might serve as supplementary food sources for most of the fishes and higher invertebrates in our systems.

Mud was one of those odd tangents that hit right around the “early 2000’s refugium craze, and sort of faded quickly into the background. I am sure that part of it was a renewed obsession later in the decade with less biodiverse, more “coral-centric” systems, which eschewed substrates in general, specifically those which had the tendency to house competing biota! All of those factors- and a continued (and cool, I might add) obsession with using high tech electronic pumps to facilitate ridiculous amounts of water movement within our aquariums sealed the fate of mud as a true reef “side show” for the foreseeable future.

Now here we are, in the fading years of the 2nd decade of the new millennium, and I think that it’s time to resuscitate the idea of using mud in our reef tanks again in some capacity. And I’m thinking not JUST the refugium. I’m talking about the display! Now, I realize that a lot of reefers will disagree with my thinking, and duly advise that sand and mud and sediment can become “nutrient sinks” and work against the smooth operation and long term prosperity of a reef. The operative word here, IMHO- is CAN. I mean, even water exchanges can be problematic if poorly executed, right? So I think it might be worth looking at how a well-managed mud/sediment/sand bed could help support a healthy, diverse closed reef ecosystem.

Now, if you go way back into the past (like 2005), you may recall some of the studies into various substrate depths and compositions (and plenums!) and their relative impact on mortality of animals in aquaria. Now, in all fairness, the test subjects were fishes and inverts like hermit crabs and snails, but the findings are nonetheless relatable, in my opinion, to reef tanks. Tonnen and Wee ran a lot of tests with different depths of substrate, ranging from very dahlia to rather deep, and the results were quite fascinating, in my opinion. Interestingly, one conclusion was that “...the shallower the sediment, the higher the mortality rate, and you can't get much shallower than a bare bottom tank!"

Again, that set of experiments had a lot of different variables, like the aforementioned plenum, as well as the use of pretty coarse substrate in some setups (Not too many of us use that stuff!),and no real test using marine muds and sediments as the sole substrate in a reef setting. However, I think it is perhaps safe to say that the presence of a substrate itself in a reef tank doesn’t spell disaster for the inhabitants- be they fish, corals, or urchins…The reality is that a well-managed, carefully stocked reef tank should work under a variety of situations.

And of course, the cautions are warranted. A poorly maintained sandbed, without some creatures present to stir up the upper layers, can prove problematic if detritus and organic wastes are allowed to accumulate unchecked, right? And there is the so-called “old tank syndrome” (Paul, you’ll have a field day with this, right?) that suggests that after some point in a reef systems operational lifetime (whatever that might be!) the bacteria population within the system (likely the sanded) is depleted somehow and/or no longer has the ability to keep up with the accumulations of organic waster products, and that phosphates and such are released back into the system.

I am probably being a jerk, and simply being biased, but I have a real problem with that theory. I just don’t see how a well-managed aquarium declines over the years. I’ve personally maintained one reef tank for 11 years, and one freshwater tank for 16 years and never had these issues. I’m not saying to nominate me for sainthood or anything, but I will tell you that I am a firm believer in not overstocking my tanks, utilizing multiple nutrient export avenues (protein skimming, activated carbon, use of macro algae/plants, and weekly water exchanges). There is no magic there.

Okay, that being said, tanks with substrate, specifically fine sediment materials like mud and such, are not “set and forget” systems. You’ll need to be actively involved. And by “actively involved”, I mean more than tweaking the lighting settings on your LEDS via your iPhone). You’ll need to get your hands wet. Which to me, is the best part of reef keeping!

Now, I’m literally just scratching the surface here, deliberately not going too deep into this because I’d like your thoughts and input. However, I think it’s absolutely possible to maintain a successful reef system with mud and other marine sediments as a significant part of the substrate. One of the keys, in my opinion, is to utilize some marine plants…you know- seagrasses.

Yep- thats’ a whole different story for another time, but I will touch on them here to open things up more. I think they are deserving of more attention from reefers.

Okay, we all have probably seen or heard about them at one time or another, but rarely do we find ourselves actually playing with them! They are not at all rare in the wild- In fact, they are found all over the world, and there are more than 60 species known to science. Seagrass beds provide amazing benefits to coral reef ecosystems, such as protection from sedimentation, a “nursery” for larval fishes, and a feeding ground for many adult fishes.. In the aquarium, they can perform many of the same functions. So why are we not seeing more of them in the hobby?

I believe there are three main reasons why we don’t: 1) They suffer from what I call the “Caulerpa Syndrome”- a bad rep ascribed to just about anything green in the marine hobby- “They will smother your corals”, or “They can crash and kill everything in the tank”, or even, “They give off toxic byproducts that inhibit coral growth”. 2) There simply aren’t enough people working with them to get them out to the hobby in marketable quantities. 3) They are finicky and hard to grow.

Let’s beat up Number 1 first: Seagrasses are true vascular plants, not macroalgae, and they do not creep over rocks, go “sexual” and crash, or exude chemicals that will stifle the growth of your “True Echinata”! In fact, they are mild-mannered, grow at a relatively modest rate, and are compatible with just about everything we keep in a reef tank. And no, they will not smother your corals or grow over rockwork. They grow in soils and sandbeds, and need to put down root systems. You can keep them nicely confined to just the places that you want them. Dedicate a section of sandbed that you’d like them to grow, plant them, give them good conditions, and you’ll be singing their praises in no time!

Reason Number 2 is probably caused in part by #1, but in actuality, is the most probable reason why we don’t see them everywhere: Until very recently, they were the sole domain of dedicated specialty hobbyists, who delighted in growing plants and taking on other challenges. The hobby as a whole simply never sees them in quantity, helping spur the (false) image that they are rare, dangerous, or difficult to work with. Someone (hey- that can be YOU) needs to step up and produce/distribute them in quantity! (if you don’t…I will, lol)

Reason Number 3 has a bit of truth to it. Some of the seagrasses can be a bit finicky at first, and don’t always take initially when transplanted. Like any plant, they go through an adjustment period, after which they will begin to grow and thrive if conditions are to their liking. It has also been discovered in recent years that there are microbial associations in the soils/sediments that they are found in which enable them to settle in better and adapt to new conditions. So in short, if you are obtaining seagrasses, you can never hurt your cause if they come with some of the substrate that they grew in.

If you can provide a mature, rich sand bed (say 3”-6”), good quality lighting (daylight spectrum or 10k work well), decent water quality, and no large populations of harsh herbivorous fishes, like Tangs or Rabbitfishes), you can almost guarantee some success. And the other key ingredient is patience. You need to leave them alone, let them acclimate, and allow them to grow on their own.

By the way, you can use a variety of commercially-available substrate materials in addition to your fish-waste-filled sand, such as products made by Kent Marine, Seachem and Carib Sea, that are designed just for this purpose! How ironic- products exist to help grow seagrasses, and so few people are actually taking advantage of them! Oh, and wait, a well-stocked reef is capable of creating a good rich sand bed, huh?

There are three main species that we find in the hobby: Halodule, or “Shoal Grass”, Halophilia , knows as “Stargrass”, “Paddle Grass”, or “Oar Grass”, and Thalassia, known commonly as “Turtle Grass”. I call them “The Big Three”. Each one has slightly different requirements, and I will briefly cover them here.

Halodule looks a lot like the freshwater plant Sagittaria, or “Micro Sword”, in my opinion- and grows like it, too. Plant it in a modestly deep (3”), rich substrate, and it will put down a dense system of runners as it establishes itself. Once it establishes itself, it’s about as easy to grow as an aquatic plant can be, IMO. I think it’s the best candidate for extensive captive propagation, so those of you with greenhouses should devote a tray or two to this stuff. I envision this being grown in “pony packs” like you see with groundcover plants at your local nursery, so that a hobbyists can purchase a “flat” of Halodule and simply plop it into their tank.. Think of the commercial possibilities here, folks!

Halophila is a very attractive plant, which, although slightly more delicate and challenging than Halodule, is still relatively easy to grow, and is really pretty, too! I’ve grown this plant in substrates as shallow as 2.5”, but you probably want 3” or more for good solid growth. This seagrass definitely “shocks out” when you transplant it, and you will lose some leaves straight away. However, with patience, good conditions, and a little time, it will come back into its own and form a beautiful addition to your reef tank. And man, it would be a nice sight to see at your next club frag swap- I’ll bet you could get a choice “Superman Monti” in trade for a few Halophila!

Thalassia is “THE” seagrass to most people- the one we envision when we hear the term “Seagrass”. It’s called “Turtle Grass”, and it is one of the larger varieties, growing up to 24” in height if space permits. Its thick leaves create a beautiful contrast to rockwork, and it can create an interesting area for fishes to forage when you can get a thick growth of it. It does grow VERY slowly, and you will typically have to start with a quite a few plants if you are trying to fill in a designated space in your tank. It requires a pretty deep sandbed, too- 5 to 6 inches or more is ideal. Because of it’s slow growth rate and height requirements, it’s the least attractive candidate for captive propagation, IMO. However, it is still a lovely plant with much to offer.

Seagrasses offer just another interesting diversion and an opportunity for the hobbyists to try something altogether new in the aquarium. Not only will you be growing something cool and exciting, you’ll have a chance to get in on the ground floor of a new area of the marine hobby. By unlocking the secrets of seagrasses, you will be further contributing to the body of knowledge of the husbandry of these plants. Obviously, I just scratched the uppermost surface of the topic here, but I’m hopeful that I have piqued your interest enough to give the seagrasses a try!

Oh, man, was that a tangent, right?

Well, not totally, because it’s my opinion that the key to a high biodiversity reef tank in the long term would be to incorporate these true vascular plants into the mix. And mangroves, too! Now, I would be fooling myself and all of you if I felt that a mangrove pant in your reef is going to contribute in any meaningful way to nutrient export for your system. Sure, they may pull some nutrient from the water or substrate, but their real value, in my opinion, is to foster the growth of epiphytic life (diatoms, tunicates, etc.) which contribute to the nutrient export and biodiversity of the aquarium.

And of course, they look cool. And I am very fascinated about playing with mangroves leaves, and the decomposing materials and how they interplay with the aforementioned sediments, and corals…There’s a lot going on there. It’s a lot to consider for a reef tank…but I can’t help but feel that there is something to be gained by incorporating mangroves into the mix…I have visited Julian Sprung’s unique and highly diverse reef systems several times, and each time I’m taken with just how well everything functions as part of a whole- plants, macroalgae, seagrass, sponges, tunicates, feather dusters, coral, invest…fishes. Real deal diversity. Truly the microcosm that John Tullock outlined so many years ago.

I’m a firm believer that people like Julian, Paul B., and others are successful with their diverse systems long term because they understand and appreciate the biodiversity, and provide conditions which allow the largest majority of life forms to prosper for the longest period of time. Also, the guys have made the “mental shift” that those of you who follow my freshwater writing here me speak of so often…The mental shift that understands and appreciates the way these systems actually look. A POV that realizes that some algae, some detritus, and some nitrate/phosphate is not only inevitable- it’s desirable. It’s a mode of thinking which gets away from the “Coral is everything and the tank must be spotless, with every technical prop used to assure this…” and embraces a mindset of “The tank must be lush and diverse, with a wide variety of animals thriving as they do in nature in a stable environment.”

Two perfectly valid mindsets, with somewhat similar goals, but dramatically different approaches to get there, and viewpoints as to which aesthetic is most attractive. I am not saying that we all need to ditch all of our high tech gear and go back to trickle filters, 5,000k halides, and massive pump-powered protein skimemrs. What I am suggesting is that we utilize the technology and information that is available today and apply it to some of the more interesting approaches from the past which foster more diverse reef systems.

The time has never been more appropriate. Time to look at some of these “niche” ideas with a new mindset- and a new appreciation for what they can accomplish!

Let’s hear your thoughts on some of these approaches and how the best parts might be incorporated into a “second decade” twenty-first century reef tank!

Stay bold. Stay curious. Stay engaged. Stay open-minded…

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman