I found this article that I wrote some time ago that was never published as it was around the time when most aquarium magazines (or at least those I was involved with) were closing down. Hopefully this is of interest to some new aquarists.

Even within the class Anthozoa, the “corals” are not a monophyletic group, with all members apart from the Hexacorallian (or Zoantharian) order Actiniaria, the sea anemones, though some would even argue that these are corals. The order Anthozoa is divided into two subclasses, the Alcyonarians (or Octocorallians) which are generally known by aquarists as soft corals, and the Zoantharians (or Hexacorallians) which contain a variety of groups known to aquarists as well as a number of extinct groups.

Many aqarists also think of zoanthids and corallimorphs as soft corals, when they are actually hexacorals and therefore more closely related to Scleractinians. These two groups lack the skeletons produced by hard corals and also lack the sclerites produced by soft corals. Both groups are largely carnivorous, a trait shared by the majority of hard corals and few soft corals.

What’s in a Name?

The use of the term “Coral” in the aquarium hobby.

The use of the term “Coral” in the aquarium hobby.

Many aquarists use the term “coral” to describe a number of different groups of animals within the phylum Cnidaria without knowing the relationship between the various groups. The mass grouping of different types of “coral” leads to misinformation regarding the selection and care of different species. Most commonly, aquarists group corals into two main groups, “soft corals” and “hard corals” where the latter possess a hard calcareous skeleton that the former do not. The follow-on from this is the idea that soft corals are easy to keep and require less light while the hard corals are more difficult to keep and require more light. This is a gross oversimplification of a much more complex group of animals.

Hard Coral vs Soft Coral - The Taxonomy

Hard Coral vs Soft Coral - The Taxonomy

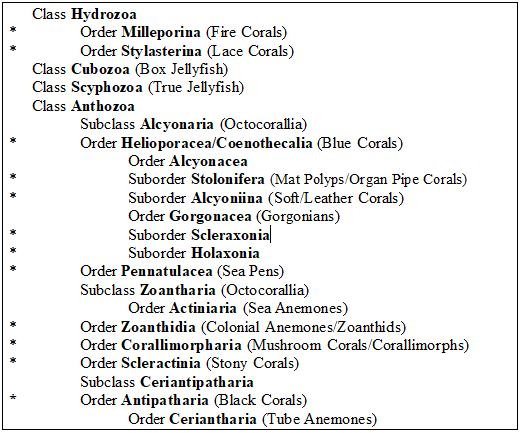

Phylogeny of the coral groups, clades marked with * are considered by aquarists to be corals. Note corals do not form a single group of entirely related organisms.

The group of animals that may be considered to be corals are not a monophyletic group, meaning there are species that share a common ancestor which do not fall into the group known as “corals”. Animals that are considered by aquarists to be corals belong to two separate classes within the phylum Cnidaria, they are Hydrozoa and Anthozoa. While the majority of animals known as corals belong to the Anthozoan class, there are two distinct groups of Hydrozoans that are kept by aquarists and often mistaken as “hard corals”. The lace corals of the family Stylasteridae such as Stylaster spp. and Distochopora spp., as well as the fire corals of the family Milleporidae with the single genus, Millepora, lay down a solid skeleton similar to that produced by the Scleractinian corals with which they are often mistaken.

The lace coral Distichopora, not dissimilar in appearance to a gorgonian or one of the many branching stony corals.

Even within the class Anthozoa, the “corals” are not a monophyletic group, with all members apart from the Hexacorallian (or Zoantharian) order Actiniaria, the sea anemones, though some would even argue that these are corals. The order Anthozoa is divided into two subclasses, the Alcyonarians (or Octocorallians) which are generally known by aquarists as soft corals, and the Zoantharians (or Hexacorallians) which contain a variety of groups known to aquarists as well as a number of extinct groups.

The octocorals as previously mentioned, are often known to aquarists as soft corals, though this is a misnomer due to the skeleton produced by a number of octocorals. While the majority of octocorals do not produce a solid calcium carbonate skeleton, a number of them produce solid calcareous skeletons that may cause them to be mistaken for hard corals. In general, the Alcyonarians produce sclerites or spicules, small calcium carbonate structures that aid in structural support of the animal or colony. The blue corals of the order Helioporacea (or Coenothecalia) produce a calcium carbonate skeleton with blue pigmentation caused by a calcium-bonded biliverdin (Dove et al, 1995), while the genus Tubipora from the order Stolonifera produce a red skeleton that is constructed using fused sclerites, a different structure to that of Scleractinians.

The mix-up of hard and soft corals does not only go one way, many aquarists see the soft fleshy tissue of many Scleractinians and, while disregarding the large skeleton that is supporting it, claim them to be soft corals. This is common in a large number of commonly available corals including Euphyllia spp., Catalaphyllia jardinei, Heliofungia actiniformis and Physogyra lichtensteini. With some of these corals, if they are not mistaken for soft corals, they are often mistaken for sea anemones. Many aquarists think of hard corals as corals that are almost entirely solid such as those from the genera Acropora, Montipora, Merulina and Porites, when the majority have large amounts of soft, fleshy tissue, usually with polyps much larger than those found in octocorals.

The mix-up of hard and soft corals does not only go one way, many aquarists see the soft fleshy tissue of many Scleractinians and, while disregarding the large skeleton that is supporting it, claim them to be soft corals. This is common in a large number of commonly available corals including Euphyllia spp., Catalaphyllia jardinei, Heliofungia actiniformis and Physogyra lichtensteini. With some of these corals, if they are not mistaken for soft corals, they are often mistaken for sea anemones. Many aquarists think of hard corals as corals that are almost entirely solid such as those from the genera Acropora, Montipora, Merulina and Porites, when the majority have large amounts of soft, fleshy tissue, usually with polyps much larger than those found in octocorals.

When fully expanded, the skeleton of Catalaphyllia jardinei is not visible and the stony coral is easy mistaken for a soft coral by many aquarists.

Many aqarists also think of zoanthids and corallimorphs as soft corals, when they are actually hexacorals and therefore more closely related to Scleractinians. These two groups lack the skeletons produced by hard corals and also lack the sclerites produced by soft corals. Both groups are largely carnivorous, a trait shared by the majority of hard corals and few soft corals.

Selection and Care – Why Mass Groupings Lead to Poor Choices

As initially mentioned, there is a widespread myth within this hobby that soft corals are easy to keep and hard corals are difficult. Firsty this is almost entirely incorrect, secondly, due to the misidentification problems already discussed, further misrepresentation occurs with respect to care. When selecting a coral for an aquarium, the difficulty level will vary even within a species based on a number of factors. Between species, difficulty level varies infinitely regardless of whether the coral is “hard” or “soft”.

Different corals react differently to transport, a coral that may thrive in a home aquarium may ship poorly and may be better left in the aquarium store a while before judging its suitability. The Alcyoniin coral Xenia and others from the same family (Xeniidae) are notoriously poor shippers, regularly ‘melting’ during transport but are also exceptionally fast growers in a variety of aquarium conditions. In Australia the Scleractinian Catalaphyllia jardinei is considered to be an easy coral for beginners but due to poor shipping rates, this coral is considered difficult to keep in other parts of the world, including the USA.

One of the most commonly used groupings by aquarists with regards to corals is the division of Scleractinian corals into two groups, “SPS” and “LPS” based purely on the polyp size of the coral. While this may be of interest in that many aquarists have a preference for small polyped corals such as those from the families Acroporidae and Pocilloporidae while others have a preference for corals with large polyps such as Euphyllia and Catalaphyllia, the grouping has little relevance with respect to the requirements of the corals. The first question that should be pondered when making these groupings is, what size determines SPS vs LPS? An example of corals that throw conjecture to the theories are those from the genus Turbinaria with species that could potentially put into either group. T. peltata is a large polyped species while T. reniformis is a small polyped species. Both species are found at similar depths and according to Veron (2000), both species are found in turbid waters suggesting polyp size has little relevance to water conditions for these corals.

The generally accepted rules are, SPS require more light and water movement, SPS require less feeding and, in general, SPS are better suited to the advanced aqurist. The first of these suggests SPS are found in shallow water where they are exposed to high energy and high light conditions. While a quick glance at an exposed reef flat would suggest this is true, it must be noted that this is not where the majority of SPS is collected. While diving with commercial collectors in Fiji, I was surprised to find most of the more commercialy viable SPS was collected at greater depths than both LPS and soft corals, depths of around 12-15m, certainly not a depth that could be considered to be a high light environment, especially compared to the lighting found on many marine aquariums. It is also generally accepted that hard corals require more light and water flow than soft corals. A close look at a tidal reef flat will show large monospecific patches of leather corals such as Sinularia and Lobophytum where they would be exposed to extreme light conditions and often very high flow conditions. These and many other soft corals produce mucous layers often as frequently as every 10 days (Borneman, 2001) which require moderate to strong water flow to remove and avoid suffocation of the coral.

The second point regarding feeding is an absolute myth, all Scleractinians require food but the difference is, not surprisingly, the size of the food items. While it is often recommended that corals with large polyps that are more anemone looking should be fed in much the same way as anemones, with large meaty foods such as whitebait, uncooked prawns or other seafood items, corals with small polyps and less obvious feeding structures should also be fed. Corals with small mouths will feed on smaller prey with suitable foods including rotifers or baby brine shrimp either frozen or live or one of the many commercially available dried foods. With LPS that do not have obvious feeding structures such as Trachphyllia or Lobophyllia, these corals can generally be fed at night or coerced into opening exposing the tentacles where they can be fed small meaty foods such as mysis shrimp or finely chopped seafood.

The third suggests that aquarists should not consider SPS corals until they have experience keeping other corals. While this is true for some species there are many notable exceptions to the rule. Some of the most difficult to keep corals are not SPS, the are in fact LPS, and even soft corals. Most of the more difficult to keep corals are aposymbiotic corals, that is, those that do not possess symbiotic algae. Corals such as Tubastrea, Dendronephthya and many commonly available species of gorgonian do not possess symbiotic algae and therefore rely on feeding and nutrient uptake from the water column to receive all of their required nutrients. Captive survival rates for these corals are far low than those of many SPS corals. The stony corals from the genera Goniopora and Alveopora are notoriously some of the most difficult corals to keep, with survival rates beyond 6 months probably lower than 1%. These LPS corals seem to fare well initially and even show growth in the short term but nearly always succumb to an unkown problem after a few months and slowly recede and die. Unfortunately, whether by lack of education or lack of care by collectors, wholesalers and retailers, these corals are readily collected and offered to aquarists, often sold as “ideal first corals” giving novice aquarists the impression these corals are easy to keep. There are on the other hand SPS corals that are very easy to keep and could be suggested for novice aquarists. While the difficulty varies greatly from species to species, generally corals from the genus Porites and several from the family Pocilloporidae are hardy corals requiring only reasonable water conditions to thrive in the home aquarium.

As with any addition to the coral reef aquarium, it is important for aquarists to research the corals they intend to add, avoiding impulse buys and identifying corals as closely to species level as possible. Retailers are generally not educated to the point most aquarists expect, many come from hobbyist level with their own area of interest and expertise, whether it is marine, cichlid or planted aquaria. The responsibility lies with the consumer to research as best they can the compatibility of the coral they select to their level of experience and expertise, the cohabitants of the aquarium and the conditions in the aquarium such as water parameters, light and water flow. Where possible, do not rely on a single point of information, especially when this information comes from overseas such as the US aquarium trade. Corals can be very basic animals to keep as long as their required conditions are met

References:

As initially mentioned, there is a widespread myth within this hobby that soft corals are easy to keep and hard corals are difficult. Firsty this is almost entirely incorrect, secondly, due to the misidentification problems already discussed, further misrepresentation occurs with respect to care. When selecting a coral for an aquarium, the difficulty level will vary even within a species based on a number of factors. Between species, difficulty level varies infinitely regardless of whether the coral is “hard” or “soft”.

Different corals react differently to transport, a coral that may thrive in a home aquarium may ship poorly and may be better left in the aquarium store a while before judging its suitability. The Alcyoniin coral Xenia and others from the same family (Xeniidae) are notoriously poor shippers, regularly ‘melting’ during transport but are also exceptionally fast growers in a variety of aquarium conditions. In Australia the Scleractinian Catalaphyllia jardinei is considered to be an easy coral for beginners but due to poor shipping rates, this coral is considered difficult to keep in other parts of the world, including the USA.

One of the most commonly used groupings by aquarists with regards to corals is the division of Scleractinian corals into two groups, “SPS” and “LPS” based purely on the polyp size of the coral. While this may be of interest in that many aquarists have a preference for small polyped corals such as those from the families Acroporidae and Pocilloporidae while others have a preference for corals with large polyps such as Euphyllia and Catalaphyllia, the grouping has little relevance with respect to the requirements of the corals. The first question that should be pondered when making these groupings is, what size determines SPS vs LPS? An example of corals that throw conjecture to the theories are those from the genus Turbinaria with species that could potentially put into either group. T. peltata is a large polyped species while T. reniformis is a small polyped species. Both species are found at similar depths and according to Veron (2000), both species are found in turbid waters suggesting polyp size has little relevance to water conditions for these corals.

The generally accepted rules are, SPS require more light and water movement, SPS require less feeding and, in general, SPS are better suited to the advanced aqurist. The first of these suggests SPS are found in shallow water where they are exposed to high energy and high light conditions. While a quick glance at an exposed reef flat would suggest this is true, it must be noted that this is not where the majority of SPS is collected. While diving with commercial collectors in Fiji, I was surprised to find most of the more commercialy viable SPS was collected at greater depths than both LPS and soft corals, depths of around 12-15m, certainly not a depth that could be considered to be a high light environment, especially compared to the lighting found on many marine aquariums. It is also generally accepted that hard corals require more light and water flow than soft corals. A close look at a tidal reef flat will show large monospecific patches of leather corals such as Sinularia and Lobophytum where they would be exposed to extreme light conditions and often very high flow conditions. These and many other soft corals produce mucous layers often as frequently as every 10 days (Borneman, 2001) which require moderate to strong water flow to remove and avoid suffocation of the coral.

The second point regarding feeding is an absolute myth, all Scleractinians require food but the difference is, not surprisingly, the size of the food items. While it is often recommended that corals with large polyps that are more anemone looking should be fed in much the same way as anemones, with large meaty foods such as whitebait, uncooked prawns or other seafood items, corals with small polyps and less obvious feeding structures should also be fed. Corals with small mouths will feed on smaller prey with suitable foods including rotifers or baby brine shrimp either frozen or live or one of the many commercially available dried foods. With LPS that do not have obvious feeding structures such as Trachphyllia or Lobophyllia, these corals can generally be fed at night or coerced into opening exposing the tentacles where they can be fed small meaty foods such as mysis shrimp or finely chopped seafood.

The third suggests that aquarists should not consider SPS corals until they have experience keeping other corals. While this is true for some species there are many notable exceptions to the rule. Some of the most difficult to keep corals are not SPS, the are in fact LPS, and even soft corals. Most of the more difficult to keep corals are aposymbiotic corals, that is, those that do not possess symbiotic algae. Corals such as Tubastrea, Dendronephthya and many commonly available species of gorgonian do not possess symbiotic algae and therefore rely on feeding and nutrient uptake from the water column to receive all of their required nutrients. Captive survival rates for these corals are far low than those of many SPS corals. The stony corals from the genera Goniopora and Alveopora are notoriously some of the most difficult corals to keep, with survival rates beyond 6 months probably lower than 1%. These LPS corals seem to fare well initially and even show growth in the short term but nearly always succumb to an unkown problem after a few months and slowly recede and die. Unfortunately, whether by lack of education or lack of care by collectors, wholesalers and retailers, these corals are readily collected and offered to aquarists, often sold as “ideal first corals” giving novice aquarists the impression these corals are easy to keep. There are on the other hand SPS corals that are very easy to keep and could be suggested for novice aquarists. While the difficulty varies greatly from species to species, generally corals from the genus Porites and several from the family Pocilloporidae are hardy corals requiring only reasonable water conditions to thrive in the home aquarium.

As with any addition to the coral reef aquarium, it is important for aquarists to research the corals they intend to add, avoiding impulse buys and identifying corals as closely to species level as possible. Retailers are generally not educated to the point most aquarists expect, many come from hobbyist level with their own area of interest and expertise, whether it is marine, cichlid or planted aquaria. The responsibility lies with the consumer to research as best they can the compatibility of the coral they select to their level of experience and expertise, the cohabitants of the aquarium and the conditions in the aquarium such as water parameters, light and water flow. Where possible, do not rely on a single point of information, especially when this information comes from overseas such as the US aquarium trade. Corals can be very basic animals to keep as long as their required conditions are met

References:

- Borneman, E. H. (2001) Aquarium Corals: Selection, Husbandry and Natural History. T. F. H. Publications. New Jersey, USA. 464pg.

- Dove, S. G., M. Takabayashi and O. Hoegh-Guldberg. 1995. The Biological Bulletin, Vol 189, Issue 3, pp 288-297

- Veron, J. E. N. 2000. Corals of the World. Australian Institute of Marine Science. Townsville, Australia. Vol 2, Pg 290-296.