We invite you all to talk about LIGHT. Come share your knowledge, your thoughts and experience with us!

original source link : https://orphek.com/lighting-the-reef-aquarium/

By Dana Riddle

There are many aspects involved in successfully husbandry of a reef aquarium, not the least of which is lighting.

This article is the first in a series that will examine this important parameter and will discuss why lighting is important, especially if the goal is to maintain photosynthetic organisms such as many coral and clam species as well as algae.

With this understanding, along with patience and dedication, it is possible to maintain a spectacular piece of a reef within your home.

The focus of this article will be on corals and why we should provide the proper amount of light – too much light can be detrimental and, in some cases, is as bad as too little light.

But first, why do we need to properly illuminate a reef aquarium at all?

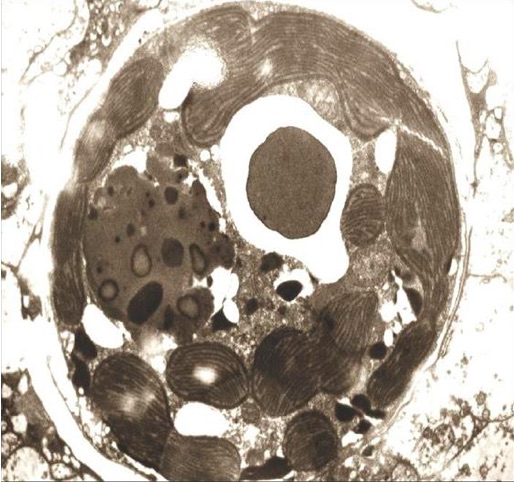

The answer is the due to the presence of microscopic ‘algae’ living within many healthy corals’ tissues. These are generally called ‘zooxanthellae’ and are of the genus Symbiodinium. See Figure 1.

Figure 1. A zooxanthella cell from a Favia stony coral. An electron micrograph taken for the author at the University of Georgia.

Years ago (in the early 1960’s) there was only one Symbiodinium species described – Symbiodinium microadriaticum.

Our knowledge has certainly increased over the years, and today we know there are at least nine described Symbiodinium species, with hundred of ‘types’ called clades (a clade is a group of things with a common ancestor.)

As any terrestrial gardener knows, there are ‘sun plants’ and ‘shade plants’ and this refers to the amount of light tolerated.

For instance, Marigolds prefer full sunlight, while Wisteria do not and are best suited for shaded areas.

The same is true for the zooxanthellae populating corals – some corals and their symbionts do well in high light while others are best suited to lower light conditions.

Fortunately, it is possible to find a compromise in an aquarium resulting in the successful maintenance of ‘sun’ and ‘shade’ zooxanthellae and their host corals.

There are two methods to achieve success as it relates to lighting.

There is the ‘copycat’ method where one mimics lighting used over a successful aquarium. This approach can certainly lead one to a nice aquarium, one full of thriving corals. But it does have drawbacks – no two aquaria are exactly alike and details that seem minor can have major – sometimes negative – impacts. The other method is one that involves a ‘scientific’ approach where light intensity is measured, and corals are placed in appropriate places within the aquarium.

There are various ways to measure light intensities.

The least expensive way is through use of a lux meter. Lux is a unit of illuminance and is equal to one lumen per square meter. Lux is a universally recognized measurement unit and is part of the International System of Units (SI.)

Maximum sunlight (at noon on a cloudless day) is about 100,000 lux. Lux is not the best way to measure light in an aquarium since a lux sensor measures light skewed towards the green portion of the spectrum.

A much better way is to measure Photosynthetically Active Radiation (PAR) through use of a quantum meter.

This meter reports the number of light particles (photons) falling upon a given surface area (usually one square meter.)

This number of photons can be enormous, so it is reported as microMol per square meter per second (µmol·m²·sec.)

Sunlight at full strength is about 2,000 µmol·m²·sec. Quantum meters are generally more expensive than lux meters.

However, it is an invaluable tool – if its purchase is beyond the means of the aquarist, perhaps the local fish club can purchase one for members’ use.

We know lighting is a critical part of a successful reef aquarium – why would one ignore measuring it?

How many successful hobbyists ignore measuring other parameters such as salinity, pH, alkalinity, or calcium? Sure, it can be done but leaves a lot to chance…

Next time, we’ll begin an examination of various light measuring devices.

original source link : https://orphek.com/lighting-the-reef-aquarium/

By Dana Riddle

There are many aspects involved in successfully husbandry of a reef aquarium, not the least of which is lighting.

This article is the first in a series that will examine this important parameter and will discuss why lighting is important, especially if the goal is to maintain photosynthetic organisms such as many coral and clam species as well as algae.

With this understanding, along with patience and dedication, it is possible to maintain a spectacular piece of a reef within your home.

The focus of this article will be on corals and why we should provide the proper amount of light – too much light can be detrimental and, in some cases, is as bad as too little light.

But first, why do we need to properly illuminate a reef aquarium at all?

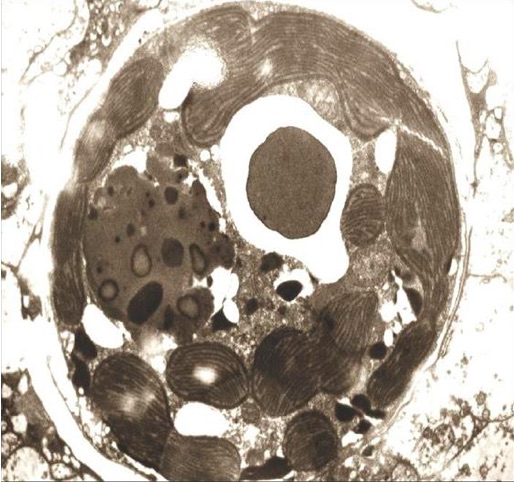

The answer is the due to the presence of microscopic ‘algae’ living within many healthy corals’ tissues. These are generally called ‘zooxanthellae’ and are of the genus Symbiodinium. See Figure 1.

Figure 1. A zooxanthella cell from a Favia stony coral. An electron micrograph taken for the author at the University of Georgia.

Years ago (in the early 1960’s) there was only one Symbiodinium species described – Symbiodinium microadriaticum.

Our knowledge has certainly increased over the years, and today we know there are at least nine described Symbiodinium species, with hundred of ‘types’ called clades (a clade is a group of things with a common ancestor.)

As any terrestrial gardener knows, there are ‘sun plants’ and ‘shade plants’ and this refers to the amount of light tolerated.

For instance, Marigolds prefer full sunlight, while Wisteria do not and are best suited for shaded areas.

The same is true for the zooxanthellae populating corals – some corals and their symbionts do well in high light while others are best suited to lower light conditions.

Fortunately, it is possible to find a compromise in an aquarium resulting in the successful maintenance of ‘sun’ and ‘shade’ zooxanthellae and their host corals.

There are two methods to achieve success as it relates to lighting.

There is the ‘copycat’ method where one mimics lighting used over a successful aquarium. This approach can certainly lead one to a nice aquarium, one full of thriving corals. But it does have drawbacks – no two aquaria are exactly alike and details that seem minor can have major – sometimes negative – impacts. The other method is one that involves a ‘scientific’ approach where light intensity is measured, and corals are placed in appropriate places within the aquarium.

There are various ways to measure light intensities.

The least expensive way is through use of a lux meter. Lux is a unit of illuminance and is equal to one lumen per square meter. Lux is a universally recognized measurement unit and is part of the International System of Units (SI.)

Maximum sunlight (at noon on a cloudless day) is about 100,000 lux. Lux is not the best way to measure light in an aquarium since a lux sensor measures light skewed towards the green portion of the spectrum.

A much better way is to measure Photosynthetically Active Radiation (PAR) through use of a quantum meter.

This meter reports the number of light particles (photons) falling upon a given surface area (usually one square meter.)

This number of photons can be enormous, so it is reported as microMol per square meter per second (µmol·m²·sec.)

Sunlight at full strength is about 2,000 µmol·m²·sec. Quantum meters are generally more expensive than lux meters.

However, it is an invaluable tool – if its purchase is beyond the means of the aquarist, perhaps the local fish club can purchase one for members’ use.

We know lighting is a critical part of a successful reef aquarium – why would one ignore measuring it?

How many successful hobbyists ignore measuring other parameters such as salinity, pH, alkalinity, or calcium? Sure, it can be done but leaves a lot to chance…

Next time, we’ll begin an examination of various light measuring devices.